Shineanthology’s Weblog

An anthology of optimistic, near future SFArchive for Near Future

Intimations of Immortality: Are We Ready for Extreme Longevity, or Do We Even Deserve It?

Although this is a rather belated nusing about a panel topic in this year’s AussieCon IV in Melbourne, I think the topic is sturdy enough to stand the test of time (Q.E.D.).

Let’s start with William Wordsworth:

The panel at AussieCon IV was “Implications of Immortality”, and the panel description was:

Immortality is a common element in science fiction and fantasy, but what would it actually be like?

What would you need to do and think about if you were immortal? How would society need to change if we were all immortal?

In a world where we are no longer faced with an end to our lives, how would human society change?

In general, I was rather disappointed by this panel (audio transcript here, courtesy of the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence), as it mostly repeated SF and fantasy’s clichés about immortality, and didn’t really reach any interesting, new (let alone ground-breaking) conclusions.

So, with this panel, and a number of internet articles about immortality — Annalee Newitz on io9 (Four Arguments against Immortality), Jason Stoddard (Four Arguments FOR Immortality), BBC’s recent Do You Really Want to Live Forever?, an interview on I Look Forward To about the possibility of immortality or extreme longevity with Aubrey de Grey and David Brin (When Will Life Expectancy Reach 200 Years?), Edward Cheever’s In Defense of Immortality — in mind, I’m going to try to deconstruct a number of faulty assumption about extreme longevity.

You may have noticed that I’m not calling it ‘immortality’ anymore. Well, I think immortality is in the same class as Utopia, infinity and perfection: a great destination to travel to, but one that can never be reached. Yet we should try, nevertheless. While immortality is an unreachable ideal, the effort of reaching it will bring huge progress and immense advantages. So let’s be a tad more realistic and call it the quest for longevity, or extreme longevity.

Problem is, a lot of people think we shouldn’t be on this quest anyway, because of several misconceptions. Let’s go through them:

(1): Humans are not ‘wired’ for immortality or extreme longevity.

As (panel member) Will McIntosh said (I’m paraphrasing here): “the human psyche is not wired for immortality: in almost every thing we do lies the shadow of our oncoming demise.” However, this assumes that humans will not change. I think humans will change. Actually, humans are already changing, and have been changing throughout history.

The problem with a lot of thinking in science fiction is that it often takes one — and only one — idea and tries to imagine its impact on humans and/or society while assuming that the latter (humans and society) do not change, or only minimally through that one single idea. In reality, though, society is an immensely complex web of connections that all influence each other.

Therefore, as such, both humans and society have changed over the years, also (among many other things) in regards to life expectancy. Life expectancy has increased (and is still increasing), and we have learned to live with that. Less than two centuries ago we would become, on average, 37 years old. Our ‘productive’ life span was 20 to 25 years. Now we get, on average, 77 years old, with a ‘productive’ life span of over 40 years.

Indeed: right now we have more ‘productive’ years than we actually lived 200 years ago. And if someone had said, back in 1810, that humans aren’t wired to live 80 years, most people would have agreed.

Well, immortality won’t happen overnight: it will take time to develop much longer lifespans, followed by extreme longevity. Time enough for humans to change, and to adapt successfully to a much longer life. People have been changing all the time — albeit at a much higher rate in the past 100 years — and have been able to cope. Why shouldn’t we be able to do so in the future?

Imagine someone in 1810 saying that in 200 years people would travel around the world regularly, that we would live twice as long, and that we would be able to talk to people at the other side of the globe through a device that weighs less than a book. Now imagine depriving your 8-year-old kid from her/his gameboy, cell phone, or internet connection.

I’ve been discussing this with (Guest of Honour) Kim Stanley Robinson at the bar right after the panel, and he thought that such thinking — humans will remain the same while the world around them changes — is ‘a failure of the imagination’. I agree: by the time extreme longevity is possible, we will have developed the right mindset for it.

However — as Annalee Newitz proposed on io9 — we may change so much that we’re no longer human. Well, try to define ‘being human’ first. Then compare that 21st Century definition with that of a 19th Century one: there will be quite a number of differences. As mentioned, humans change, and the yardstick that ‘defines’ humanity changes, as well.

Of course, Annalee voiced the fear that we might become emotionless monsters as we develop extreme longevity. I disagree: there have been monsterous humans throughout history, Stalin, Hitler and Pol Pot just a recent addition to a long, long list that stretches back to the dawn of human memory. Yet we have always overcome these monsters: why shouldn’t we be able to do that in the future?

I’ll even go a step further: it makes much more sense to be a ruthless dictator and burn all your bridges behind you if your lifespan is short. Conversely, if you realise that you have several centuries to go, it makes little sense to rampage an ecology that you need to support your much longer life. Even beter, as longer lifespans (or even extreme longevity) spread throughout the world population (and it will: see point 3 of this post), then it is in everybody’s best interest to weed out those so hell-bent on power that they are willing to destroy a very long term infrastructure (like say, Gaia) for it.

(Not to mention the non-starter ‘Whatever body you’re in, there you are‘. Sorry: last time I looked all of us are constrained to one, and one body only. I personally will highly appreciate it if it lasts much, much longer.)

(2): Immortality is boring: I will be stuck with the same dead-end job/uninteresting life/pointless existence forever.

As mentioned, immortality is an idealised concept: it is an endpoint that we might approach asymptotically, hence it will not happen overnight. Still, quite a few people (some of which were in the audience of the panel) seem to think so. One even literally mentioned that ‘immortality would be a kind of eternal hell as she would be stuck with the same dead-end job forever’.

In the grander scheme of things, holding a steady job throughout one’s carreer may already be a passing fad in times to come. Yes, in times of yore one — before the 20th Century almost always a man — acquired (either through education, experience, inheritance or a combination thereof) a job or profession and stuck to it for the rest of one’s productive life. Exceptions acknowleged, of course, but those were few and far in between.

But nowadays, things are different, completely different, just check out this video: “Shift Happens: Bringing Education into the 21st Century”

A few price quotes:

—1 out of 4 workers today is working for a company they have been employed by for less than one year

—More than 1 out of 2 are working for a company they have worked for for less than five years

…the top 10 in demand jobs for 2010 did not exist in 2004

—We are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist…

…using technologies that haven’t been invented…

…in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet

Basically, the amount of jobs that you can hold for your complete productive life is shrinking: a ‘job-for-life’ is increasingly becoming a feature of the past.

Therefore, in order to keep making a living people already need to keep educating themselves, constantly. I know what I’m talking about: I train people in my company’s product, and I need to stay updated. I teach and I learn, all the time.

Some people see this as a bad thing: such people like to keep on doing the same things, ad nauseam until their pension. This, though, is increasingly not an option anymore.

I see this as an interesting, and potentially good development: now people (must) keep developing themselves, learning new things, broadening their horizons, expanding both the depth and the breadth of their knowledge.

Isn’t this an exhilarating convergence? As life expectancy grows, life is becoming more interesting, as well. Maybe we are already on the right track to leading longer and more fullfilling lives by being able to change constantly?

Now before some of you — like Athena Andreadis (see point 2) — start to argue that the memory and learning capacity of a human brain is limited, let me make a bet (for a drink, or a symbolic amount like one Euro): I bet that before people live so long that their brain capacity is insufficient to store, work or even understand all the knowledge they build up in their extended lifetime, that there will be not one, but a variety of competing options to extend that brain capacity. For example, check out Andy Clark’s article “Out of Our Brains” in the New York Times (via Futurismic).

(3): Only the superrich will have immortality, and will keep it ‘locked away’ from the rest of the world.

Or point 4 (“We’ll have to deal with the immortality divide“) of Annalee Newitz’s io9 post.

This argument assumes that:

- there is an immediate development that changes life expectancy immensely;

- that this — nearly instantaneous — development is so expensive that only the superrich can afford it;

- that the superrich elite will be able to keep this development completely to themselves;

Personally, I suspect it’s extremely unlikely that a ‘silver bullet’ for highly increased longevity (let alone extreme longevity and forget about immortality) will be developed overnight. It’s hugely more likely that longevity will increase in leaps and bounds, with all kinds of dead alleys, red herrings and fool’s gold (to deftly mix metaphors) along the way. The way almost all scientific research does. The way longevity has been increasing already.

So while I do expect that there will be new treatments that lengthen lifespan, I do, very strongly, suspect that these will not stay with the ultra-healthy among us for long.

Consider: there are about a thousand billionaires in the world right now. There are about 10 million millionaires. By 2030, about two billion new people may join the world middle class (via Goldman Sachs: opens PDF file): adding this to the 1.5 billion middle class people as of 2010, this will total 3.5 billion middle class incomes.

So a big pharmaceutical company would keep its product exclusive to the happy thousand? Even after it has earned back its development costs? And will ignore the 10 million plus other, rich customers? And once the treatment has been proven to work for over a million people, they will not eventually want to sell it to almost 4 billion more customers? That’s not how capitalism works, last time I looked.

Then there is the case of the ghost having escaped the bottle: in science, once something has been proven to be possible, it can be replicated. If an experiment can’t be verifiably repeated, it’s not true science. So if it’s possible (extreme longevity, even immortality) then competing scientists will know that, and they will redouble their efforts to reproduce the same result.

Once a certain development’s time has come, it shows up everywhere. Tesla’s and Marconi’s dispute about who invented radio first is one example. The rise of aviation (once the Wright brothers delivered proof of concept) is another. There are countless more. And these technologies, once new, are now available to almost everybody: radio (is become obsolete by the internet, another technology initially developed for the hapy few — the Pentagon or CERN— available to all), avaition, the utmost majority of modern medicine. Once the cat is out of the bag…

Competition, the desire to sell it to as much markets as possible, the fact that it can be done all will make sure that it eventually becomes available to all. Inevitably.

(4): (a) Biological immortality or biological extreme longevity is impossible; and (b): mind uploading is a pipe dream.

Check out this interview with Aubrey de Grey and David Brin: When Will Life Expectancy Reach 200 Years?

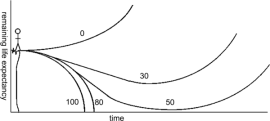

The above gentlemen are talking about a life expectancy of 200 years. While that may sound already unrealistic to some, and a bit unambitious to others (what is 200 years in the face of extreme longevity?), there is a tipping point. As Ronald Bailey explains in his Liberation Biology:

“Researcher reported in the April 2002 issue of Science that life expectancy has been increasing at about two and a half year per decade for the past 160 years. Demographers such as Olshansky, they note, have been consistently wrong in predicting an upper limit to this trend. In 1928, for example, demographer Louis Dublin predicted that average life expectancy in the United States would never exceed 64.75 years. Today it is 77.6 years.”

“At this rate of improvement, the authors of the Science report conclude that “record [average] life expectancy will reach about 100 in six decades”.”

It gets better:

De Grey offers a scenario in which efforts to achieve radical life extension reach “actuarial escape velocit (AEV)”. Recall that for the last 160 years, average life expectancy has increased by two-and-a-half year per decade. What if increases in life expectancy rose at a rate of ten years or more per decade? “The escape velocity cusp is closer than you might guess,” claims de Grey. “Since we are already so long lived, even a thirty percent increase in healthy life span will give the first beneficiaries of rejuvenation therapies another twenty years—an eternity in science—to benefit from second generation therapies that could give another thirty percent, and so on ad infinitum”

Yes, the same Aubrey De Grey interviewed above. The above quote can be found online on PLoS Biology: ‘Escape Velocity: Why the Prospect of Extreme Human Life Extension Matters Now‘.

Extreme longevity in this century? Maybe even in our lifetime?

As noted above, David Brin disagrees, as I’m sure many of you do. “There are way too many obstacles,” I hear you say, “there is no low-hanging fruit.” Further cue to David Brin:

All advances to date have involved allowing ever-greater percentages of humanity to hit the “wall” at age 100, and maybe coast a few years beyond. Getting beyond that will require either;

1) THOROUGH nanotechnology, applied down at the INTRA-cellular level, or

2) genetic recoding to enhance repair capabilities in new ways (good news for our great grandchildren, maybe), or

3) gradual replacement of failing parts and systems with prosthetics, or

4) uploading.Oh, I am willing to be proved wrong, but all of these seem much harder than the zealots think.

a) The intra-cellular world is the next frontier. It now seems huge, complex, involving massive amounts of computing. Will you flood the INSIDES of cells with nanomachines? Good luck.

b) We haven’t a clue how to do #2.

c) #3 will happen in phases. But when the brain fades… well,… see #a

c) re #4 — see #a

(Emphasis mine.)

The Aubrey De Grey/David Brin interview was posted on November 25, 2010. Three days later, this news came out: “Harvard Scientists Reverse the Ageing Process in Mice“. Price quote:

The Harvard group focused on a process called telomere shortening. Most cells in the body contain 23 pairs of chromosomes, which carry our DNA. At the ends of each chromosome is a protective cap called a telomere. Each time a cell divides, the telomeres are snipped shorter, until eventually they stop working and the cell dies or goes into a suspended state called “senescence”. The process is behind much of the wear and tear associated with ageing.

At Harvard, they bred genetically manipulated mice that lacked an enzyme called telomerase that stops telomeres getting shorter. Without the enzyme, the mice aged prematurely and suffered ailments, including a poor sense of smell, smaller brain size, infertility and damaged intestines and spleens. But when DePinho gave the mice injections to reactivate the enzyme, it repaired the damaged tissues and reversed the signs of ageing.

This sounds very much like ‘genetic recoding to enhance repair capabilities in new ways’. And yes, it is only applicable to mice (“Repeating the trick with humans will be more difficult”), and developing a method that works for humans might still be a long way off. Yet, we have gone from “We haven’t a clue how to do #2” to “We have found a method that works in mice”.

So while extreme longevity is probably not around the corner, I believe that it is possible. At the very least we can expect that our life span will continue to increase in the future, as it has done for the past 160 years. Very probably with more than 2-and-a-half year per decade. I strongly suspect that auctuarial escape velocity will not be a matter of if, but of when.

And then extreme longevity is a fact of life.

Finally, as to (b): mind uploading is a pipe dream;

I don’t know.

On the one side, the human brain is an immensely complex organ, of which we still understand very little (even though our knowledge is increasing). It’s also very unclear if a mind based so intimately in a biological body can be ‘transported’ or ‘copied’ to a non-biological mainframe, without considerable losses in either functionality or memory or both.

On the other side, if Moore’s Law holds (and it’s not showing any signs of slacking up yet), then by the time mind uploading is possible — even when it happens only a few decades from now — then there will be a hell of a lot of computing power available to upload into.

Apart from that, if uploading becomes possible, there is still the problem that, in all likeliness, it will be copying your mind into a different substrate, leaving the original behind to die. That’s why I prefer developments of extending lifespan of our biological bodies: it seems the better bet.

Picture credits:

- Blue Trefoil Knot: via Wikipedia;

- Shift Happens: via Shifting Paradigms;

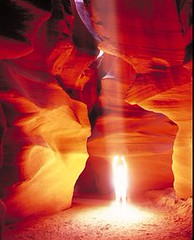

- Intimations: via Photography Blog;

- Intimations of Immortality: via The Millstone;

- Actuarial Escape Velocity: from the PLoS Biology article;

- Golden Trefoil Sculpture: via Into the Deep;

Utopia: A Vindication?

As the second comment (by Paul Graham Raven) already noticed, maybe I could see Charlie Stross’s post about Utopia as a kind of vindication?

[Picture: Vindication Island: a destination, never to be reached, like Utopia?]

[Picture: Vindication Island: a destination, never to be reached, like Utopia?]

For one, science fiction in general is—again, see the huge catch-up exercise called cyberpunk ( the punk label itself was already a few years outdated back in 1983, which indicates how pathetic the ‘punk’ label sounds in steampunk, dieselpunk, mythpunk and what-have-you-punk. Where is SF’s imaginative use of neologisms when you really need it?) when SF belatedly realised it had been neglecting these dang computers for too long—behind the curve: see, for example, last year’s four-issue special called Blueprint for a Better World that New Scientist featured from September 12 until October 3 in 2009.

In other words—and I have already voiced this almost ad nauseam here on this blog—while SF wallows in its dystopias, gloom’n’doom scenarios and total apocalypses, people in (gasp) the real world are already looking for solutions to our problems.

I am already tired of SF fandom’s idea that science fiction should inspire science, or the real world. It has been the other way around, mostly, and increasingly overwhelmingly in the past few decades.

What use does an African boy have for apocalyptic science fiction if he wants to build to a better future? Why would people in rural Bangladesh need to read the latest eco-disaster if they are visited by the InfoLadies instead? People in the real world aren’t longing for depictions of dystopia to show them how it shouldn’t be done: they’re way too busy to improve their own lot.

So, in the larger scheme of things, it’s probably a minor vindication for an idea—optimistic SF, *not* Utopia—whose idea seems finally, and belatedly to be entering the SF writing community’s mindset.

{BTW: not Utopia. the term ‘Utopia’ alone is a button-pusher in the science fiction crowd, immediately unleashing the all-too-predictable clichés: “Utopias are booooooooring”, “There can be no conflict in Utopian stories” (hence, when I demonstrate that conflicts are part and parcel of a near-future, optimistic SF story—one needs to overcome big hurdles to achieve improvements—Kathryn Cramer laments that ‘SHINE delivers (mostly) happy endings in dystopias rather than actual utopian speculation‘: true, as I never intended SHINE to be a plethora of Pollyannas), “Dystopias are the signs of the future saying ‘do not go there’.” (so in which direction should we go? We only need negative incentives?), “One man’s Utopia is another man’s Dystopia”, Etcetera, ad nauseam.}

For another, this review gives me much more vindication:

Anyway, just about a textbook example of how to do it […]

I thought this book would be decent – so when it hits around the excellent mark and is a great price currently you really should buy it.

Having read hundreds of anthologies it isn’t often that I want to revisit one soon afterwards, Shine is definitely one such.

Finally, an editorial remark. To quote Blue Tyson from the above-mentioned review:

Interestingly, he says most of the writers around are pathetically incapable of writing a story along these lines – which is odd, given as they say, ideas are a dime a dozen.

Unfortunately, this is true. I have sollicited many, very many of today’s well-known SF writers for Shine, and the utmost majority of them wouldn’t or couldn’t (or shouldn’t?) produce a near-future, optimistic SF story. One in particular—whose name shall remain unknown—telling me that ‘near-future SF is mind-numbingly hard these days’.

So there you go: is near-future, optimistic SF too hard to do, or are contemporary SF writers suffering from—and here I’m quoting another well-known SF author, with whom I discussed this at a recent WorldCon—”a failure of the imagination”?

To be continued, I hope…

Tentative Steps Forward: West Africa, North Australia, San Francisco, Brazil, the World

Sometimes I can’t help but wonder why—in the SF blogosphere —a post about whether SF should or should not die effortlessly draws more eyeballs than near-future SF stories that demonstrate its relevance. Partly, I suspect, because stories do not contain links to other articles. Still, it’s a bit of a shame that articles with a negative undertone get more attention than stories with a positive message. Or maybe I’m just comparing apples to pears.

Therefore an article about positive developments in the world (I’ve already posted plenty of those). Here’s one development that particularly caught my attention, because it is a solution that addresses several problems at the same time:

→In West Africa, native fruits have a big future:

(from New Scientist, November 7, 2009. Yes, it’s six weeks old, and I’m catching up on my NS reading. But this is an item that will remain relevant for—at least—several decades, showing that near-future, optimistic SF does not need to have a one or two-year expiration date.)

For those not subscribing to New Scientist, the article is online.

To quote:

“Domesticating wild fruit like bush mango has changed our lives.”

“It is a peasant revolution taking place in the fields of Africa’s smallholders.”

In short, African farming smallholders are switching to local wild fruits, making both more food and more money, and creating more biodiversity and environmental sustainability in the process.

The advantages combine to make a sum larger than the separate parts:

- fruit trees exist in a large variety (over 300 different ones in Cameroon alone);

- fruit trees are much better resistant against droughts than mass crops like cassava, maize and wheat;

- in the domestication programme, local knowledge and science—after some initial mistrust, which was overcome by the good results—are combined;

- all low-tech, no fancy equipment needed;

- fruit trees generate income year-round (not just three months like, for example, cacao);

- they thrive in a diversity situation (many different tree crops on one land), creating a habitat for wildlife and environmental sustainability;

- people not only get better food, but with the extra income they buy school fees for their children, decent healthcare, and improved housing;

Let’s call it ‘win/win squared’!

Obviously, there is still a very long way to go, and there will be large obstacles to overcome—especially worries about a level playing field against big agriculture: check out some of the comments in the comment section—but this is nevertheless a tentative step forward, not only in Africa, but it’s happening in North Australia, as well (see also some of the comments in the comment section of the article).

A similar interesting development is the rise of urban beekeeping as honeybee numbers have been falling to catastrophic levels, with the counter-intuitive result that people in cities are helping to keep honeybees alive, both genetically and increasingly in larger numbers. Many thanks to Cameo Wood—who runs Her Majesty’s Secret Beekeeper in the Mission District—for informing me about this when she showed Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman and me around in San Francisco, courtesy of Borderlands Books.

These are just two examples of how important changes can arise from small origins, and not necessarily need to come from big technological shifts.

These are just two examples of how important changes can arise from small origins, and not necessarily need to come from big technological shifts.

By way of contrast, two examples of implementing change directly on the larger scale (keeping in mind that the previous examples are already adding up in sheer numbers):

- Growing biofuel without razing the rainforest (also via New Scientist): an interview with plant scientist Marcus Buckeridge;

- The 2009 Human Development Report: common migration misconceptions are challenged (“Migration can be a force for good, contributing significantly to human development,” says United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Administrator Helen Clark.)

To restate (as I’ve done over and over on this site): good things and optimistic developments are happening on this planet: they’re just underreported, underrated and—I suspect—underestimated. Let’s keep looking forward, and work on a better future.

Should SF Die?

(Cross-posted to my personal blog and the DayBreak Magazine site for those who prefer a more Spartan layout.)

There’s been a lot of musing about the fate of science fiction, lately. To be clear, I’ll be discussing *written SF* here (predominantly), not SF in movies, comics, video games or other media. To summarise (and this is far from complete, but I hope it touches upon the main points):

- According to Ashok Banker, SF is morally and ethically bankrupt (to put it mildly: his interview at the World SF News Blog has been deleted on his request, because some idiot stalker is now threatening not only him, but his family and friends, as well);

- According to Lavie Tidhar, SF — and fantasy, as well — is suffering from monolithic anglophone syndrome;

- According to Mark Newton, SF is commercially dead, and fantasy is the (bestselling) future;

- According to Athena Andreadis on the Huffington Post, SF has ditched science and has become, in effect, fantasy. Geoff Ryman (who recently edited When It Changed) and Ken MacLeod (who is involved with The Human Genre Project) seem to agree;

My viewpoint is that SF is becoming increasingly irrelevant, and that lack of relevance can be attributed to developments and trends already mentioned in the points above, and SF’s unwillingness to really engage with the here-and-now. That doesn’t mean that SF needs to die (actually, a slow marginalisation into an increasingly neglected and despised niche-cum-ghetto is probably a fate worse than death), but it does mean that SF needs to change, and that it needs to become much more inclusive of the alien (and I mean alien in ‘humans-can-be-aliens-to-each-other’ sense) and proactive, meaning it should not just shout ‘FIRE! FIRE!’ (and do almost nothing but), but both man the fire trucks *and* think of ways to prevent more fires.

That’s the short version: allow me to expand on it below the cut. Read the rest of this entry »

That’s the short version: allow me to expand on it below the cut. Read the rest of this entry »

Kindred Spirits, part 9

In all the kerfuffle I haven’t failed to notice Terry Bison’s interview with Kim Stanley Robinson (regular visitors know I’ve quoted the man several times on this site already). Io9 summarised it as “Dystopian Fiction Is For Slackers“, and while I mostly agree — while acknowledging that there are great dystopias, I think the form itself has become too much of an easy writing mode and a cliché — I think it oversimplifies matters.

As Kim Stanley Robinson said on the New Scientist website earlier this year, science fiction tends to see the pessimism/optimism duality too much as an either/or phenomenon, while in real life things are much more complex: they’re a mix of upbeat and downbeat, with indifference, incomprehensibility and interconnectedness thrown in for good measure, and also strongly subjective; that is dependent on and coloured by one’s personal experience, mindset and perspective.

And indeed, while he calls it ‘utopia’, what he means is not a full-on, happy clappy Pollyanna:

So, the writing of utopia comes down to figuring out ways of talking about just these issues in an interesting way; how tenuous it would be, how fragile, how much a tightrope walk and a work in progress.

This, BTW, describes the majority of the stories in both the Shine anthology and DayBreak Magazine. One clear example that you can already read is David D. Levine’s “horrorhouse“, that perfectly demonstrates ‘how tenuous, fragile’ such a ‘utopia’ (I prefer to call it a ‘better future’, meaning there’s always room for improvement, with ‘utopia’ as the ideal that can never quite be reached) is: both a ‘tightrope walk’ and always a ‘work in progress’.

Finally, I take note that if people thought that I overstated my case with the “Why I Can’t Write a Near-Future, Optimistic SF Story: the Excuses” piece (which keeps consistently getting several dozens of hits each day), well, Kim Stanley Robinson doesn’t exactly pull his punches, either:

The political attacks are interesting to parse. “Utopia would be boring because there would be no conflicts, history would stop, there would be no great art, no drama, no magnificence.” This is always said by white people with a full belly. My feeling is that if they were hungry and sick and living in a cardboard shack they would be more willing to give utopia a try.

Amen to that.

(Or, as I said: “And indeed, that’s what most dystopias are: a comfort zone for unambitious writers”.)

While some do see the opportunities in utopias (and watch this space come March 19, 2010), others immediately feel the need to defend dystopias. As if these, like climate change, need defending.

Anyway, one small blessing has already occurred: new e-zine Bull Spec — whose first short is by Terry Bisson, indeed who did the ‘utopia’ interview: coincidence? — already changed their guidelines to include utopias on the theme:

“utopias are hard, and important, because we need to imagine what it might be like if we did things well enough to say to our kids, we did our best, this is about as good as it was when it was handed to us, take care of it and do better. Some kind of narrative vision of what we’re trying for as a civilization.”

(Which is a straight quote from the Galileo Dreams interview.) So one more market — keep track: such markets are thin on the ground — where to send an optimistic story (when they re-open on February 1 next year).

Apropos David D. Levine’s “horrorhouse“, another interesting ‘coincidence’: a few days ago New Scientist put an article called “How reputation could save the Earth“, where the influence of maintaining a good reputation is wielded to extract good (eco-friendly) behaviour:

If information about each of our environmental footprints was made public, concern for maintaining a good reputation could impact behaviour. Would you want your neighbours, friends, or colleagues to think of you as a free rider, harming the environment while benefiting from the restraint of others?

Compare this to the EcoBadge in David’s story, which was published 17 days before the New Scientist article, demonstrating that near-future SF can both be trend-setting and not age immediately.

Kindred Spirits, part 7

Via a Shine contributor (I’m not saying who. I’m not giving the ToC just yet. There will be a competition about this) I was attended to GreenPunk. I see their blog started last August 19, so it’s still early days. FWIW, my first impressions:

- Their manifesto (or ‘statement of purpose’) is a bit too formal (and occasional over-the-top: see point C) for my taste. Caveat: I’m not a fan of manifestos. When Jason Stoddard wrote a manifesto about optimistic SF, I immediately asked him to change it to an open forum; that is, open to questioning and change. Where everybody can contribute and discuss, and is clearly and openly invited to do so. Hence the Optimistic SF Open Platform on the top of this very site.

- I agree with several of the commenters on the io9 topic about GreenPunk: why punk? I’m so tired of -punk added to a movement. Worked with cyberpunk. Got repetitive with steampunk. Got boring with clockpunk. Got completely superfluous with every whateverpunk after that.

- A flog to make sure the horse stays dead: the original punk movement got tired of itself by the early eighties already. Punk is dead, it’s become a product, and proclaiming your movement as ‘GreenPunk’ is about as realistic as the mohawk of the guy pictured below:

- (Yes, you can buy it — for $7.89 to look cool at the next Halloween)

- Finally — this punkhorse resurrects more often than vampires and zombies combined, unfortunately — punk is what beginning musicians produce because they can’t really play their instruments. The moment they do acquire a certain level of musicianship they start to play different music like gothic rock, hardcore and maybe eventually even metal.

Anyway, as mentioned, it’s still very early days for GreenPunk (they’re live less than a month), so time will tell if they are here to stay and produce something interesting (says the guy whose Shine blog is still a month away from its first anniversary. Life on the web is short and fast…;-). As long as they don’t go the way of the SFFEthics-that-became-the-SFFEnthusiasts, whose blog hasn’t posted anything since June 30 (says the guy who hardly posted anything last August. My excuses are a total solar eclipse in China, a WorldCon in Canada, a hacker conference in my home country, preparing for an important new project on the day job and the fact that I had to deliver the Shine MS on August 31. To say that I was extremely busy in August is an understatement: it was totally insane).

BSFA‘s Matrix Online (good to see that it’s running again after a short hiatus) has — among many other things — posted an article about Shine by Sissy Pantelis. Check it out, and thanks, Sissy!

To follow up on the “Blueprint for a Better World” post: New Scientist has posted 8 SF stories — edited by Kim Stanlay Robinson — online, calling them sci-fi: the fiction of now.

It’s typical: while I was busy writing up my piece about how the Shine anthology is coming together for SF Signal, I also thought about these 8 flash fiction pieces. I can’t help but think that most of these stories go against the spirit of what New Scientist is trying to do with the “Blueprint for a Better World” series: only Ian McDonald’s “A Little School” is somewhat, very cautiously optimistic, but the rest varies from pessimistic satires to outright apocalyptic (Geoff Ryman’s “2019: The Reality?”, Nicolla Groffith’s “Acid Rain“, Paul McAuley’s “Penance” and Stephen Baxter’s “Kelvin 2.0“). As mentioned, even the satirical pieces (Ian Watson’s “A Virtual Population Crisis“, Justina Robson’s “One Shot” and Ken McLeod’s “Reflective Surfaces” [what’s in a name…;-)]) are downbeat in tone.

It’s typical: while I was busy writing up my piece about how the Shine anthology is coming together for SF Signal, I also thought about these 8 flash fiction pieces. I can’t help but think that most of these stories go against the spirit of what New Scientist is trying to do with the “Blueprint for a Better World” series: only Ian McDonald’s “A Little School” is somewhat, very cautiously optimistic, but the rest varies from pessimistic satires to outright apocalyptic (Geoff Ryman’s “2019: The Reality?”, Nicolla Groffith’s “Acid Rain“, Paul McAuley’s “Penance” and Stephen Baxter’s “Kelvin 2.0“). As mentioned, even the satirical pieces (Ian Watson’s “A Virtual Population Crisis“, Justina Robson’s “One Shot” and Ken McLeod’s “Reflective Surfaces” [what’s in a name…;-)]) are downbeat in tone.

While I agree that it, more or less, indeed represents a proportional cut-through of the state of current written SF (overwhelmingly downbeat), I can’t help but think that it goes against the spirit of the “Blueprint for a Better World” series.

Which is, I suspect — as I am still catching up with everything, so just read today — summed up New Scientist‘s own editorial of the August 22 issue, which I would love to quote ad verbatim, but will have to refrain, and take out the tastiest morsels:

Positive thinking for a cooler world

[…] Show people this video and they will find little motivation not to carry on generating trah and burning oil like there’s no tomorrow. But tell them about the steps their peers are taking to make things better, and they may just follow suit. […]

[…] Over at the Earth Day Network site, it gets worse. There you can find how many Earths it would take to support your lifestyle if everyone on Earth lived the same way. It’s hard to find any positive messages: a vegan who doesn’t own a car, never flies, takes public transport to work and shares a tiny appartment in a US city would still be told their lifestyle requires 3.3 Earths. It is hard to see what this is going to achieve, other than disillusioning people who are already doing their bit and telling everyone else that it isn’t worth the bother […]

(Emphasis mine.) This almost exactly echoes the points I made on the “Why I Can’t Write a Near-Future, Optimistic SF Story: the Excuses” post, especially the Sixth Excuse:

Furthermore, with the amount of cautionary tales going around in SF today, we should be well on our way to paradise, as we’re being told ad nauseam what not to do. Imagining things going wrong is easy; imagining things improving is hard. It’s easier to destroy than create. I’m sick and tired of writers demonstrating five thousand different ways of destroying a house: I long for the rare few that show me how to repair it, or build a better one.

Oh well: New Scientist tries to lead by example. Will SF follow suit? Let a thousand Shines rise…

Blueprint for a Better World

Which is literally what New Scientist is saying in their weekly newletter to me (and I’m a longtime subscriber), here.

I know I’ve said this before (a lot of times, maybe to the point of ad nauseam), but I’m afraid it needs to be repeated, especially for a lot of thick-headed people in SF: people around the world want more than just the next doomsday scenario telling them what happens of we carry on doing the *stupid* things: what they really want (and need) is a pointer to solutions.

I know I’ve said this before (a lot of times, maybe to the point of ad nauseam), but I’m afraid it needs to be repeated, especially for a lot of thick-headed people in SF: people around the world want more than just the next doomsday scenario telling them what happens of we carry on doing the *stupid* things: what they really want (and need) is a pointer to solutions.

I really need to refrain from quoting the whole piece (“Blueprint for a Better World“) verbatim. But it’s what I’ve been saying on this very blog from the get-go. Like:

We live in an imperfect world. Poverty, disease, lack of education, environmental destruction – the problems are all too obvious. Many people don’t have clean water, let alone enough food, and the unsustainable lifestyle of the wealthy few is storing up catastrophic climate change.

Can we do anything about it? You bet we can. Technology is a double-edged sword, but science and reason have made our lives immeasurably better overall – and only through science and reason can we hope to make a real difference in the future. So here and over the next three weeks, New Scientist will explore diverse ideas for making the world a better place, and the evidence backing them.

Almost exactly as in some stories in Shine, [in part 1 this week] “we look at some radical ideas for transforming society and changing the way countries are run”.

[Next week in part 2] “We’ll report on what you as an individual can do to make a difference.” I can point to a few other stories in Shine.

[In part 3] “We’ll explore what many see as the fundamental problem: overpopulation.” Kill me, shoot me and throw me to the wolves, but please check out The Elephant in the Room: a Foreshadowing (from December 1, last year) first.

[In part 4] “We’ll ponder the profound and long-lasting changes we are making to our home planet.” Again, I can point to several Shine stories.

Yes, I’ve delivered the final MS (manuscript) to Solaris Books. The people at Solaris are now very busy with the owner transition I mentioned in the previous post. So while I’m awaiting more info from them (release date, for one), I am confident that they will publish Shine (as per contract, and—more importantly—per intent). Apologies for the lack of replies in the past week, as I am working on several other things, which will become clear as they happen.

And no apologies as I need to ram home the really important thing: the majority of SF, and the majority of written SF in particular, sees no need in portraying a future ‘where people might actually like to live in’ (as Gardner Dozois has it in the July 2009 Locus). On the other hand, the most popular weekly scientific journal in the world DEDICATES FOUR ISSUES TO DEPICT “A BLUEPRINT FOR A BETTER WORLD”.

Now who is out of touch here?

Now who is out of touch here?

I’m very, very happy with what New Scientist is doing right now. I would be completely ecstatic if Shine would appear right after that, but it seems it’ll be early 2010. Compared by how fast written SF moves, though, it’ll still be bleeding edge.

Kindred Spirits, part 6

It’s either running or standing still with the observation of kindred spirits: for weeks I notice nothing, then I see three (UPDATE: nay, five) in a single day.

Here’s what caught my eye:

- Bruce Sterling, in Beyond the Beyond, names 18 challenges for contemporary literature. I’ll highlight number 10 (which IMHO links to my previous musings on relevant SF):

10. Contemporary literature not confronting issues of general urgency; dominant best-sellers are in former niche genres such as fantasies, romances and teen books.

- Expanded Horizons: a webzine that has the inclusion of non-western, and non WASP-male viewpoints as it’s mission;

- The website of Haikasoru, the new Japanese SF line of VIZ media, has some very interesting observations by Nick Mamatas, to quote:

I will now give a definitive answer despite my lack of expertise (yay Internet!)—Japanese SF is fresher and more enthusiastic than American SF.

and:

Japanese SF, especially the near-future material, is somewhat more interested in expressing hopes for international cooperation than is American SF.

- Dresden Codak: a webcomic (infrequently updated) by Aaron Diaz stuffed to the brim with nerdy goodness like physics, philosophy, robot girls, impending singularities and more. Hard to resist a heroine (Kimiko) who is — in a game called Dungeons and Discourse — an ‘8th level positivist’ who casts ‘techno-utopianism’ — and whose mother — in part 21 of Hob — tells her the following:

(Mother) “Are you excited about going to America?”

(Young Kimiko) “No. Why do we have to leave?”

(Mother) “Oh, I think we just scared the wrong kind of people.”

(Young Kimiko) “Who?”

(Mother) “People who lack vision. They only see the obvious. They see the sun go down, but they don’t see it rise.”

- The Don’t Look Back comic of Dicebox aside. Patrick Farley‘s on a (rock’n’)roll here with a dizzying crossover of 70s psychedelica & SF, space guitars with nothing but captains, freaks & uptights, prog & Prague, the green sun & choiciest choices. As infrequently updated as Dresden Codak, unfortunately, but at least as much fun. Unlike Hob, it hasn’t reached the end yet, and I’m eagerly awaiting more from this Apocalyptic Utopian.

Interesting times!

An Update on the Shine Submissions, part 1

Well, not sure if there will be a part 2, but just in case.

Anyway, over the past couple of days I’ve been writing responses to the first one hundred (102 to be precise) unsollicited submissions I’ve received so far. I’ve now responded to all submissions up until May 28, except for a single one of which I haven’t made up my mind.

Two breakdowns, one by suitablility and one by setting (and keep in mind that both breakdowns add up to *more* than 102 as for some stories more than one [un]suitability factor applies or as some have more than one setting):

By Suitability; number of stories that are:

1) Not Suitable (in general): 41

2) Dystopia Lite: 14

3) Technofix: 9

4) Flight Forward: 16

5) Alien Saviours: 15

6) Superheroes Save the Day: 8

7) Hold/Rewrite Request (held over for a second read, rewrite or serious consideration): 8

(A small clarification: Dystopia Lite = First the world goes to the dogs, but in the end there is a small light at the end of the tunnel [and I’m deliberately using the American (mis)spelling here as this is also basically soothes the effect of a problem rather than addressing the cause]; Technofix = A lone genius invents cold fusion/universal nanotech/immortality/whatever and all our problems are solved (this is a variation of the old deus ex machina); Flight Forward = We go into space, without solving the problems we have on Earth [note that the latter is true for all examples 2 up to 5]; Alien Saviours = Alien intervention will solve/has caused our problems. )

Then there are stories that have the right intention, but use a flawed or clichéd execution, like:

–How people from the future (or an alternate reality) show the protagonist how the world will go down the drains unless she/he mends her/his ways (already old since the days of Charles Dickens);

–A future where outer appearances have changed (people have become animal hybrids, androids, half-robots or uploaded avatars) while internally they’re still the (bickering) same;

–How machines (robots, AIs, car accessories, household appliances, sexual aids) learn to really understand the human condition (where the underlying moral unvariably teaches how superior humans are: I strongly suspect, however, that an artificial intelligence that’s truly more intelligent than humans would either be very sad or laugh itself silly);

–How humanity will be accepted by enlightened aliens if they just pass this test;

–And even *several* stories that combine future medical developments with basebal;

By Setting; number of stories that are set in:

–USA: 54

–Canada: 9

–UK: 7

–France: 3

–Rest of Europe: 4

–Latin America: 4

–Asia: 1

–Australia/Pacific: 1

–Space: 18

–Imaginary Setting: 2

Now a few tips on how to increase your chances of acceptance (apart from the bleedingly obvious, that is: write a superb story):

- Try to come up with a story where things actually change for the better with respect as to how they are now. A story that implements a solution for one of the great problems of our time, or that dies trying. And no: starting with an apocalypse and then showing a little light at the end of the tunnel (see point 2 above: ‘dystopia lite’) does not count: that world is, in general, much worse off than we are today;

- Try to come up with a story where humanity itself (partly) changes; that is: where humans change their behaviour, voluntarily, in order to address a huge problem (or several huge problems). As noted above, in the majority of stories I’ve seen so far either no big problems are addressed at all (Dystopia Lite, Flight Forward), or something else (Technofix) or someone else (Alien Saviours) does it for us, so we don’t change and haven’t learned a thing. In my viewpoint, SF is the literature of *change*, ideally of unexpected, deep-seated, paradimg-shifting change, both internally *and* externally;

- Be ambitious: most stories only change a minor thing for the better, as if the author was too afraid to tackle the really big subjects. If the antho would be an accurate reflection of the slushpile, then it would be full of nice little stories where good things happen to decent people. That might be very plausible, but is also boring as hell. I highly prefer to get a story that’s incredibly audacious, reaches for the sky, and spectacularly fails rather than all the competent ones that barely take any risk at all. Dare to be gloriously wrong!

- A setting that’s not in the western world. As is clear from the above count, less than 6% of the stories I get are set in the developing world, while I would very much like to see such settings represented in Shine;

- Similarly, while I do get about 40% of the stories seen from a female point of view, I would dearly love to see more stories from the viewpoint (or with main characters) of people of colour (I received only four of those, so far, of which two are held over) and from a GLBT standpoint (I received two of those, and am considering both seriously);

- Finally, I’ve only seen five humourous stories, so far. While most of the Shine anthology will be serious (although a light tone or funny moment won’t hurt), I do intend to add a few humourous stories for both variety and light relief.

As I hope is very clear now: I would like to see variety, as much variety as possible within the remit of the anthology. So not just optimistic, near future SF stories set in North America or Europe, but also those set in the other continents. Not just white males solving (or trying to solve) our problems, but females, PoC and GLBT characters fighting the good fight, as well.

It’s why I’m doing a series of “Optimism in Literature around the World, and SF in particular“, and inviting people from all over the world to contribute. It’s why I’m mentioning places like Chili, the Pacific, Africa and the Islam world in my “Crazy Story Ideas” series. It’s why I’m doing the @outshine Twitterzine: to demonstrate in miniature what I have in mind.

Finally, a few remarks about the dystopias I see in the Shine slushpile (one would expect that an anthology that clearly proclaims that it’s looking for near future, *optimistic* SF would not get dystopias. Well, see point X above: you’d be quite wrong) and dystopias versus utopias in general.

The lovers of doom, gloom & apocalypse never tire to mention that utopias, in general, are naïve at best and extremely implausible at worst. Yet those same critical minds accept, without a second thought, that everybody in that dystopian setting (and I don’t care what caused the apocalypse: nuclear war, huge asteroid impact, massive volcano eruption, floods, catastrophic climate change, whatever) is armed to the teeth.

Think about it for a minute: the whole modern infrastructure has come down, people are starving and have almost (or already partly) turned to cannibalism, hardly have any decent clothes or housing to speak of, yet there is no shortage of guns. Rather the contrary: in your average dystopia, both the heroes and the villains have more weapons, and often highly sophisticated futuristic weaponry like plasma guns, fragmentation bombs and even rocket launchers in abundance. Your average street gang would drool at the weaponry those dystopian people have at their disposal.

And nobody runs out of ammunition, ever. Somehow, as the modern industrial complex has come crashing down, weapon factories keep running at top production. And no ragnarok aficionado ever calls that naïve or extremely implausible.

You can quote me for saying that the average dystopia is at least as implausible as your average utopia. Both are extreme extrapolations that will never happen in reality. Yet the verisimilitude of the former is never questioned, while the credibility of the latter is always called into doubt.

Crazy Story Ideas, part 2

Since this is the ‘crazy story ideas’ topic, let’s head to an area where precious few have gone before, and imagine — even less people have gone there — a prosperous future for it (or at least a future where things change for the better): Africa.

Since this is the ‘crazy story ideas’ topic, let’s head to an area where precious few have gone before, and imagine — even less people have gone there — a prosperous future for it (or at least a future where things change for the better): Africa.

Often referred to a ‘the lost continent’. Or, to quote:

The only thing Africa has left is the future.

Marita Golden (1950 – ) / U.S. writer and teacher / A Woman’s Place.

First, let’s not see it as a ‘lost’ continent, and take hope (and lessons) from these newsbits:

- A Victory for democracy in Africa (from CNN).

- Women getting so fed up with their men’s (political) bickering in Kenia that they have started a ‘sex strike‘.

They say they want to avoid a repeat of the violence which convulsed the country after the late-2007 elections.

- Time: Amid Global Doom, Good News from Africa: the salient quote:

That dynamic ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and today “there’s a new generation of Africans who are now saying, ‘No — show us what you can deliver,’ ” says Farhan. “They are getting their message across. You find autocrats are reincarnating themselves as democrats. They are increasingly no longer in control. It’s really interesting. There’s a new mood sweeping Africa.”

- Or, as this 2008 end-of-year report on PRI.org indicates: while the bad news — which was most prominently featured — came from Zimbabwe and the Congo, this was, according to US amabassador Charles Stith: “It really is at the end of the day the tail wagging the dog … cause the numbers speak for themselves — you’ve got 16 countries with 650 million people out of 800 million, so the vast majority of people are in countries that are on track. The good news is that the numbers of states that are coming on-line, in terms of issues of governance and the economy, is increasing.”

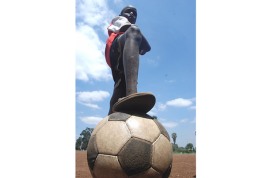

- The World Championships Football of 2010 will be held in South Africa. This cannot be underestimated: football is, by far, the most popular sport in the world, and while its darker side (hooliganism) is well known, it also inspires hope and creates joy worldwide;

Next, let’s explore Africa’s potential:

Next, let’s explore Africa’s potential:

- “Saharan sun to power European supergrid“, from the The Guardian almost a year ago (July 22, 2008; and I read the same news in a recent issue of New Scientist a few weeks ago, here is the same news on the Times online of March 15, 2009, so the idea isn’t quite that new);

- Africa’s (relative) lack of infrastructure can be an advantage, in a similar way as the Dialectics of progress (originally coined as “De wet van de remmende voorsprong” by Dutch historian Jan Romein in 1935):

- Thus, instead of large energy-generating plants with a huge power infrastructure and electricity grid, they can develop small local power plants based on solar, wind or water energy and biomass;

- Small, cheaply produced water purification units can supply clean water locally;

- In a similar manner, internet access can be done via WiFi (also no large cabling infrastructure needed): the mobile phone is already paving the way for this, as the number of the number of African mobile subscribers surpassed those in America already in May 2008;

- For transport, they can use/develop zeppelins instead of using planes, trains & automobiles (each of which need, again, a huge infrastructure: a zeppelin needs no rail, road or runways, and is energy efficient);

- Finally,the equator runs through Africa, so it’s a prime location for a space elevator base;

Obviously, there are enormous obstacles to overcome, political, cultural, sociological and technological. The challenges are huge, but I like to think that a lot of people tend to underestimate the possibility of change. A few examples: in the early eighties nobody — me included — would have believed that the Iron Curtain would come down, peacefully, in 1991. Similarly (see the Tutu quote below),

Improbable as it is, unlikely as it is, we are being set up as a beacon of hope for the world.

Desmond Tutu (1931 – ) / South African clergyman and civil rights activist / The Times (London).

hardly anybody would have believed that apartheid (one of the the best-known and ugliest Dutch words) would come to an end, starting with the release of Nelson Mandela in February 11, 1990, and ending — after several years of negotiations — with the election in 1994.

Finally, until very recently, nobody would have believed that the US would elect a black president (even if it took eight years of grandiose misgovernment and the biggest economic crisis since 1929 to help pave the way: sometimes, unfortunately, things need to get worse — even much worse — before they get better). So, in that vein:

One shouldn’t offer hope cheaply.

Ben Okri (1959 – ) / Nigerian novelist, short-story writer, and poet, 1992.

Isn’t SF about imagining the (seemingly) impossible? Write about an Africa that changes for the better (actually, I know about one writer who already does: but I swear I already had written most of this post before we talked about this at EasterCon), and send it my way.

When hope dies, what else lives?

Ama Ata Aidoo (1942 – ) / Ghanaian writer / Our Sister Killjoy, or Reflections from a Black-Eyed Squint.

UPDATE: well, I’ll be darned! The moment I post this, this news arrives: Africans Must Travel to the Moon. Although Uganda President Yoweri Museveni’s reasons —

“The Americans have gone to the moon. And the Russians. The Chinese and Indians will go there soon. Africans are the only ones who are stuck here,” Museveni said, addressing a meeting of the Uganda Law Society in Entebbe.

“We must also go there and say: ‘What are you people doing up here?’.”

— may sound a bit awkward, they do resonate, in a local, African version, my notion of how building a space elevator might help solve Earth-based problems:

“Uganda alone cannot go to the moon. We are too small. But East Africa united can. That is what East African integration is all about,” he said. “Then we can say to the Americans: ‘What are you doing here all alone?’.”

Museveni has campaigned — very vocally — for a common East African economic and political zone. Hey, SF writers: take this cue from today before the near future runs away from you!

UPDATE 2: I don’t know how I missed this, but here are some links and remarks about Africa’s so-called ‘Cheetah generation’. So, a bit late to the game (brought to my attention via ‘Ondernemen 2.0, nu ook in Afrika‘ [“Entrepreneurship 2.0, now also in Africa”] in de Volkskrant), I think a good place to start is Rob Salkowitz’s article on Internet Evolution “Africa’s ‘Cheetah Generation’ Rises on the Net“.

A few salient points:

- Since 2006, Africa has been gaining new Internet connections faster than any other region — a curve that’s only expected to steepen with the widespread deployment of mobile Web and wireless satellite-based services. Costs continue to fall, extending access further and further down the economic pyramid.

- Nearly 45 percent of a total population of 160 million Nigerians is under the age of 15, for example. In The Economist‘s “Ageing” index, which measures the ratio of under-15s to over-60s in country populations, 14 of the 15 youngest countries in the world are African.

- Now, the rapid spread of information and communication technology (ICT) and a more entrepreneurial approach to the problems of bottom-of-the-pyramid populations is turning the 20th century liability of “too many mouths to feed” into the 21st century asset of “millions of minds at work.”

Compare this with another salient point made by Vijay Mahajan at This Is Africa in his ‘Travels with the Cheetah Generation‘ article (and keep in mind that Mahajan is a Professor of Marketing, so basically he’s looking at Africa as a big business opportunity, not as a continent that needs aid):

It would come as a surprise to many — it did to me — that Africa’s economic strength is greater than India’s, which has a comparable population. If Africa were a single country, according to World Bank data, it would have had $978bn in total gross nation income in 2006. This places it ahead of all the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) except China. Africa has greater wealth than most think.

At the time of this update, SHINE has been released and contains two stories set in Africa (which are, alas, not by African authors. If I can do a follow-up, this is one thing I certainly hope to correct): “Sustainable Development” by Paula R. Stiles and “Paul Kishosha’s Children” by Ken Edgett. The former sees hope for Africa’s future beginning on a small scale, the latter even sees it become a leading continent in the future. Which ties in with Alastair Reynolds (also a SHINE contributor)’s planned 11K trilogy where Africa also becomes the leading continent in the future.

Looking at the Cheetah Generation and various other developments, that assumption may not be as far-fetched as many of you probably think. To illustrate that, another quote from Mahajan’s article:

Another statistic about Africa relates to the diaspora. With perhaps 100 million members around the globe, the diaspora is investing billions of dollars annually on the continent. And unlike the recent past, Africans living abroad are more likely to return home to lead and create new businesses. They are helping to propel Africa’s rise.

As it is, the eponymous Paul Kishosha in Ken Edgett’s story is an African living abroad who returns home and creates — if not a new business — something new and inspiring, indeed.