Shineanthology’s Weblog

An anthology of optimistic, near future SFArchive for Optimism

Intimations of Immortality: Are We Ready for Extreme Longevity, or Do We Even Deserve It?

Although this is a rather belated nusing about a panel topic in this year’s AussieCon IV in Melbourne, I think the topic is sturdy enough to stand the test of time (Q.E.D.).

Let’s start with William Wordsworth:

The panel at AussieCon IV was “Implications of Immortality”, and the panel description was:

Immortality is a common element in science fiction and fantasy, but what would it actually be like?

What would you need to do and think about if you were immortal? How would society need to change if we were all immortal?

In a world where we are no longer faced with an end to our lives, how would human society change?

In general, I was rather disappointed by this panel (audio transcript here, courtesy of the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence), as it mostly repeated SF and fantasy’s clichés about immortality, and didn’t really reach any interesting, new (let alone ground-breaking) conclusions.

So, with this panel, and a number of internet articles about immortality — Annalee Newitz on io9 (Four Arguments against Immortality), Jason Stoddard (Four Arguments FOR Immortality), BBC’s recent Do You Really Want to Live Forever?, an interview on I Look Forward To about the possibility of immortality or extreme longevity with Aubrey de Grey and David Brin (When Will Life Expectancy Reach 200 Years?), Edward Cheever’s In Defense of Immortality — in mind, I’m going to try to deconstruct a number of faulty assumption about extreme longevity.

You may have noticed that I’m not calling it ‘immortality’ anymore. Well, I think immortality is in the same class as Utopia, infinity and perfection: a great destination to travel to, but one that can never be reached. Yet we should try, nevertheless. While immortality is an unreachable ideal, the effort of reaching it will bring huge progress and immense advantages. So let’s be a tad more realistic and call it the quest for longevity, or extreme longevity.

Problem is, a lot of people think we shouldn’t be on this quest anyway, because of several misconceptions. Let’s go through them:

(1): Humans are not ‘wired’ for immortality or extreme longevity.

As (panel member) Will McIntosh said (I’m paraphrasing here): “the human psyche is not wired for immortality: in almost every thing we do lies the shadow of our oncoming demise.” However, this assumes that humans will not change. I think humans will change. Actually, humans are already changing, and have been changing throughout history.

The problem with a lot of thinking in science fiction is that it often takes one — and only one — idea and tries to imagine its impact on humans and/or society while assuming that the latter (humans and society) do not change, or only minimally through that one single idea. In reality, though, society is an immensely complex web of connections that all influence each other.

Therefore, as such, both humans and society have changed over the years, also (among many other things) in regards to life expectancy. Life expectancy has increased (and is still increasing), and we have learned to live with that. Less than two centuries ago we would become, on average, 37 years old. Our ‘productive’ life span was 20 to 25 years. Now we get, on average, 77 years old, with a ‘productive’ life span of over 40 years.

Indeed: right now we have more ‘productive’ years than we actually lived 200 years ago. And if someone had said, back in 1810, that humans aren’t wired to live 80 years, most people would have agreed.

Well, immortality won’t happen overnight: it will take time to develop much longer lifespans, followed by extreme longevity. Time enough for humans to change, and to adapt successfully to a much longer life. People have been changing all the time — albeit at a much higher rate in the past 100 years — and have been able to cope. Why shouldn’t we be able to do so in the future?

Imagine someone in 1810 saying that in 200 years people would travel around the world regularly, that we would live twice as long, and that we would be able to talk to people at the other side of the globe through a device that weighs less than a book. Now imagine depriving your 8-year-old kid from her/his gameboy, cell phone, or internet connection.

I’ve been discussing this with (Guest of Honour) Kim Stanley Robinson at the bar right after the panel, and he thought that such thinking — humans will remain the same while the world around them changes — is ‘a failure of the imagination’. I agree: by the time extreme longevity is possible, we will have developed the right mindset for it.

However — as Annalee Newitz proposed on io9 — we may change so much that we’re no longer human. Well, try to define ‘being human’ first. Then compare that 21st Century definition with that of a 19th Century one: there will be quite a number of differences. As mentioned, humans change, and the yardstick that ‘defines’ humanity changes, as well.

Of course, Annalee voiced the fear that we might become emotionless monsters as we develop extreme longevity. I disagree: there have been monsterous humans throughout history, Stalin, Hitler and Pol Pot just a recent addition to a long, long list that stretches back to the dawn of human memory. Yet we have always overcome these monsters: why shouldn’t we be able to do that in the future?

I’ll even go a step further: it makes much more sense to be a ruthless dictator and burn all your bridges behind you if your lifespan is short. Conversely, if you realise that you have several centuries to go, it makes little sense to rampage an ecology that you need to support your much longer life. Even beter, as longer lifespans (or even extreme longevity) spread throughout the world population (and it will: see point 3 of this post), then it is in everybody’s best interest to weed out those so hell-bent on power that they are willing to destroy a very long term infrastructure (like say, Gaia) for it.

(Not to mention the non-starter ‘Whatever body you’re in, there you are‘. Sorry: last time I looked all of us are constrained to one, and one body only. I personally will highly appreciate it if it lasts much, much longer.)

(2): Immortality is boring: I will be stuck with the same dead-end job/uninteresting life/pointless existence forever.

As mentioned, immortality is an idealised concept: it is an endpoint that we might approach asymptotically, hence it will not happen overnight. Still, quite a few people (some of which were in the audience of the panel) seem to think so. One even literally mentioned that ‘immortality would be a kind of eternal hell as she would be stuck with the same dead-end job forever’.

In the grander scheme of things, holding a steady job throughout one’s carreer may already be a passing fad in times to come. Yes, in times of yore one — before the 20th Century almost always a man — acquired (either through education, experience, inheritance or a combination thereof) a job or profession and stuck to it for the rest of one’s productive life. Exceptions acknowleged, of course, but those were few and far in between.

But nowadays, things are different, completely different, just check out this video: “Shift Happens: Bringing Education into the 21st Century”

A few price quotes:

—1 out of 4 workers today is working for a company they have been employed by for less than one year

—More than 1 out of 2 are working for a company they have worked for for less than five years

…the top 10 in demand jobs for 2010 did not exist in 2004

—We are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist…

…using technologies that haven’t been invented…

…in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet

Basically, the amount of jobs that you can hold for your complete productive life is shrinking: a ‘job-for-life’ is increasingly becoming a feature of the past.

Therefore, in order to keep making a living people already need to keep educating themselves, constantly. I know what I’m talking about: I train people in my company’s product, and I need to stay updated. I teach and I learn, all the time.

Some people see this as a bad thing: such people like to keep on doing the same things, ad nauseam until their pension. This, though, is increasingly not an option anymore.

I see this as an interesting, and potentially good development: now people (must) keep developing themselves, learning new things, broadening their horizons, expanding both the depth and the breadth of their knowledge.

Isn’t this an exhilarating convergence? As life expectancy grows, life is becoming more interesting, as well. Maybe we are already on the right track to leading longer and more fullfilling lives by being able to change constantly?

Now before some of you — like Athena Andreadis (see point 2) — start to argue that the memory and learning capacity of a human brain is limited, let me make a bet (for a drink, or a symbolic amount like one Euro): I bet that before people live so long that their brain capacity is insufficient to store, work or even understand all the knowledge they build up in their extended lifetime, that there will be not one, but a variety of competing options to extend that brain capacity. For example, check out Andy Clark’s article “Out of Our Brains” in the New York Times (via Futurismic).

(3): Only the superrich will have immortality, and will keep it ‘locked away’ from the rest of the world.

Or point 4 (“We’ll have to deal with the immortality divide“) of Annalee Newitz’s io9 post.

This argument assumes that:

- there is an immediate development that changes life expectancy immensely;

- that this — nearly instantaneous — development is so expensive that only the superrich can afford it;

- that the superrich elite will be able to keep this development completely to themselves;

Personally, I suspect it’s extremely unlikely that a ‘silver bullet’ for highly increased longevity (let alone extreme longevity and forget about immortality) will be developed overnight. It’s hugely more likely that longevity will increase in leaps and bounds, with all kinds of dead alleys, red herrings and fool’s gold (to deftly mix metaphors) along the way. The way almost all scientific research does. The way longevity has been increasing already.

So while I do expect that there will be new treatments that lengthen lifespan, I do, very strongly, suspect that these will not stay with the ultra-healthy among us for long.

Consider: there are about a thousand billionaires in the world right now. There are about 10 million millionaires. By 2030, about two billion new people may join the world middle class (via Goldman Sachs: opens PDF file): adding this to the 1.5 billion middle class people as of 2010, this will total 3.5 billion middle class incomes.

So a big pharmaceutical company would keep its product exclusive to the happy thousand? Even after it has earned back its development costs? And will ignore the 10 million plus other, rich customers? And once the treatment has been proven to work for over a million people, they will not eventually want to sell it to almost 4 billion more customers? That’s not how capitalism works, last time I looked.

Then there is the case of the ghost having escaped the bottle: in science, once something has been proven to be possible, it can be replicated. If an experiment can’t be verifiably repeated, it’s not true science. So if it’s possible (extreme longevity, even immortality) then competing scientists will know that, and they will redouble their efforts to reproduce the same result.

Once a certain development’s time has come, it shows up everywhere. Tesla’s and Marconi’s dispute about who invented radio first is one example. The rise of aviation (once the Wright brothers delivered proof of concept) is another. There are countless more. And these technologies, once new, are now available to almost everybody: radio (is become obsolete by the internet, another technology initially developed for the hapy few — the Pentagon or CERN— available to all), avaition, the utmost majority of modern medicine. Once the cat is out of the bag…

Competition, the desire to sell it to as much markets as possible, the fact that it can be done all will make sure that it eventually becomes available to all. Inevitably.

(4): (a) Biological immortality or biological extreme longevity is impossible; and (b): mind uploading is a pipe dream.

Check out this interview with Aubrey de Grey and David Brin: When Will Life Expectancy Reach 200 Years?

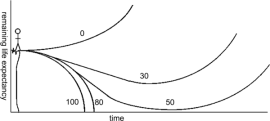

The above gentlemen are talking about a life expectancy of 200 years. While that may sound already unrealistic to some, and a bit unambitious to others (what is 200 years in the face of extreme longevity?), there is a tipping point. As Ronald Bailey explains in his Liberation Biology:

“Researcher reported in the April 2002 issue of Science that life expectancy has been increasing at about two and a half year per decade for the past 160 years. Demographers such as Olshansky, they note, have been consistently wrong in predicting an upper limit to this trend. In 1928, for example, demographer Louis Dublin predicted that average life expectancy in the United States would never exceed 64.75 years. Today it is 77.6 years.”

“At this rate of improvement, the authors of the Science report conclude that “record [average] life expectancy will reach about 100 in six decades”.”

It gets better:

De Grey offers a scenario in which efforts to achieve radical life extension reach “actuarial escape velocit (AEV)”. Recall that for the last 160 years, average life expectancy has increased by two-and-a-half year per decade. What if increases in life expectancy rose at a rate of ten years or more per decade? “The escape velocity cusp is closer than you might guess,” claims de Grey. “Since we are already so long lived, even a thirty percent increase in healthy life span will give the first beneficiaries of rejuvenation therapies another twenty years—an eternity in science—to benefit from second generation therapies that could give another thirty percent, and so on ad infinitum”

Yes, the same Aubrey De Grey interviewed above. The above quote can be found online on PLoS Biology: ‘Escape Velocity: Why the Prospect of Extreme Human Life Extension Matters Now‘.

Extreme longevity in this century? Maybe even in our lifetime?

As noted above, David Brin disagrees, as I’m sure many of you do. “There are way too many obstacles,” I hear you say, “there is no low-hanging fruit.” Further cue to David Brin:

All advances to date have involved allowing ever-greater percentages of humanity to hit the “wall” at age 100, and maybe coast a few years beyond. Getting beyond that will require either;

1) THOROUGH nanotechnology, applied down at the INTRA-cellular level, or

2) genetic recoding to enhance repair capabilities in new ways (good news for our great grandchildren, maybe), or

3) gradual replacement of failing parts and systems with prosthetics, or

4) uploading.Oh, I am willing to be proved wrong, but all of these seem much harder than the zealots think.

a) The intra-cellular world is the next frontier. It now seems huge, complex, involving massive amounts of computing. Will you flood the INSIDES of cells with nanomachines? Good luck.

b) We haven’t a clue how to do #2.

c) #3 will happen in phases. But when the brain fades… well,… see #a

c) re #4 — see #a

(Emphasis mine.)

The Aubrey De Grey/David Brin interview was posted on November 25, 2010. Three days later, this news came out: “Harvard Scientists Reverse the Ageing Process in Mice“. Price quote:

The Harvard group focused on a process called telomere shortening. Most cells in the body contain 23 pairs of chromosomes, which carry our DNA. At the ends of each chromosome is a protective cap called a telomere. Each time a cell divides, the telomeres are snipped shorter, until eventually they stop working and the cell dies or goes into a suspended state called “senescence”. The process is behind much of the wear and tear associated with ageing.

At Harvard, they bred genetically manipulated mice that lacked an enzyme called telomerase that stops telomeres getting shorter. Without the enzyme, the mice aged prematurely and suffered ailments, including a poor sense of smell, smaller brain size, infertility and damaged intestines and spleens. But when DePinho gave the mice injections to reactivate the enzyme, it repaired the damaged tissues and reversed the signs of ageing.

This sounds very much like ‘genetic recoding to enhance repair capabilities in new ways’. And yes, it is only applicable to mice (“Repeating the trick with humans will be more difficult”), and developing a method that works for humans might still be a long way off. Yet, we have gone from “We haven’t a clue how to do #2” to “We have found a method that works in mice”.

So while extreme longevity is probably not around the corner, I believe that it is possible. At the very least we can expect that our life span will continue to increase in the future, as it has done for the past 160 years. Very probably with more than 2-and-a-half year per decade. I strongly suspect that auctuarial escape velocity will not be a matter of if, but of when.

And then extreme longevity is a fact of life.

Finally, as to (b): mind uploading is a pipe dream;

I don’t know.

On the one side, the human brain is an immensely complex organ, of which we still understand very little (even though our knowledge is increasing). It’s also very unclear if a mind based so intimately in a biological body can be ‘transported’ or ‘copied’ to a non-biological mainframe, without considerable losses in either functionality or memory or both.

On the other side, if Moore’s Law holds (and it’s not showing any signs of slacking up yet), then by the time mind uploading is possible — even when it happens only a few decades from now — then there will be a hell of a lot of computing power available to upload into.

Apart from that, if uploading becomes possible, there is still the problem that, in all likeliness, it will be copying your mind into a different substrate, leaving the original behind to die. That’s why I prefer developments of extending lifespan of our biological bodies: it seems the better bet.

Picture credits:

- Blue Trefoil Knot: via Wikipedia;

- Shift Happens: via Shifting Paradigms;

- Intimations: via Photography Blog;

- Intimations of Immortality: via The Millstone;

- Actuarial Escape Velocity: from the PLoS Biology article;

- Golden Trefoil Sculpture: via Into the Deep;

Utopia: A Vindication?

As the second comment (by Paul Graham Raven) already noticed, maybe I could see Charlie Stross’s post about Utopia as a kind of vindication?

[Picture: Vindication Island: a destination, never to be reached, like Utopia?]

[Picture: Vindication Island: a destination, never to be reached, like Utopia?]

For one, science fiction in general is—again, see the huge catch-up exercise called cyberpunk ( the punk label itself was already a few years outdated back in 1983, which indicates how pathetic the ‘punk’ label sounds in steampunk, dieselpunk, mythpunk and what-have-you-punk. Where is SF’s imaginative use of neologisms when you really need it?) when SF belatedly realised it had been neglecting these dang computers for too long—behind the curve: see, for example, last year’s four-issue special called Blueprint for a Better World that New Scientist featured from September 12 until October 3 in 2009.

In other words—and I have already voiced this almost ad nauseam here on this blog—while SF wallows in its dystopias, gloom’n’doom scenarios and total apocalypses, people in (gasp) the real world are already looking for solutions to our problems.

I am already tired of SF fandom’s idea that science fiction should inspire science, or the real world. It has been the other way around, mostly, and increasingly overwhelmingly in the past few decades.

What use does an African boy have for apocalyptic science fiction if he wants to build to a better future? Why would people in rural Bangladesh need to read the latest eco-disaster if they are visited by the InfoLadies instead? People in the real world aren’t longing for depictions of dystopia to show them how it shouldn’t be done: they’re way too busy to improve their own lot.

So, in the larger scheme of things, it’s probably a minor vindication for an idea—optimistic SF, *not* Utopia—whose idea seems finally, and belatedly to be entering the SF writing community’s mindset.

{BTW: not Utopia. the term ‘Utopia’ alone is a button-pusher in the science fiction crowd, immediately unleashing the all-too-predictable clichés: “Utopias are booooooooring”, “There can be no conflict in Utopian stories” (hence, when I demonstrate that conflicts are part and parcel of a near-future, optimistic SF story—one needs to overcome big hurdles to achieve improvements—Kathryn Cramer laments that ‘SHINE delivers (mostly) happy endings in dystopias rather than actual utopian speculation‘: true, as I never intended SHINE to be a plethora of Pollyannas), “Dystopias are the signs of the future saying ‘do not go there’.” (so in which direction should we go? We only need negative incentives?), “One man’s Utopia is another man’s Dystopia”, Etcetera, ad nauseam.}

For another, this review gives me much more vindication:

Anyway, just about a textbook example of how to do it […]

I thought this book would be decent – so when it hits around the excellent mark and is a great price currently you really should buy it.

Having read hundreds of anthologies it isn’t often that I want to revisit one soon afterwards, Shine is definitely one such.

Finally, an editorial remark. To quote Blue Tyson from the above-mentioned review:

Interestingly, he says most of the writers around are pathetically incapable of writing a story along these lines – which is odd, given as they say, ideas are a dime a dozen.

Unfortunately, this is true. I have sollicited many, very many of today’s well-known SF writers for Shine, and the utmost majority of them wouldn’t or couldn’t (or shouldn’t?) produce a near-future, optimistic SF story. One in particular—whose name shall remain unknown—telling me that ‘near-future SF is mind-numbingly hard these days’.

So there you go: is near-future, optimistic SF too hard to do, or are contemporary SF writers suffering from—and here I’m quoting another well-known SF author, with whom I discussed this at a recent WorldCon—”a failure of the imagination”?

To be continued, I hope…

SHINE sighted in the wild

As the launch date for SHINE is approaching (March 30 in the USA, April 16 in the UK), several copies (contributor’s, reviewer’s, promotional) are already making their way.

So in order to whet your appetite, here are a few sightings:

Contributors:

- Gareth Lyn Powell & Aliette de Bodard (in the comments) have received it;

- Jason Andrew is quite impressed with it;

- It has come all the way to Pavonis Mons, even if not by balloon (the new blog of Al Reynolds: check it out!);

- Mari Ness got it, and was somewhat irked by seeing that her name is misspelled in the page headers (which I didn’t see in the proofs): my apologies, Mari;

- Gord Sellar thinks it’s shiny;

- Jacques Barcia tweeted it;

Promotional/review:

- John Scalzi has received it (and announces it will be featured in “The Big Idea” early April);

- Jeff VanderMeer is charmed by the pretty (see his picture below);

- Niall Alexander of the Speculative Scotsman mentions it here;

- Charles A. Tan mentions it shortly (among an overview of international SF) on the SFWA site;

- Mike Johnstone shortly mentions it at the end of his ‘saving science fiction from itself‘ post;

- Harry Markov of the Temple Library has put it on their wishlist;

- (UPDATE): Jason Sanford calls SHINE ‘the most eagerly awaited anthology of 2010;

- (UPDATE 2): Charles A. Tan made it his ‘international speculative fiction highlight‘;

- (UPDATE 3): Liz de Jager, according to her tweet, ‘is really enjoying it‘;

Obviously, as reviews appear I will link to them. Do feel free to point me to them (the good, the bad or the ugly).

Furthermore, as the release date comes closer, I will be posting an excerpt of each SHINE story here, every other day (I’ve already started doing it bi-weekly at DayBreak Magazine). More promotional actions are in the works: keep an eye out here and at DayBreak Magazine.

For those going to Odyssey (the 2010 EasterCon): all of you are cordially invited to the SHINE launch party at the Royal C+D on Saturday April 3, from 18.00 hrs. onwards. As a party organiser, I have a reputation to uphold, so do come by: I promise you won’t leave thirsty!

Also, via Jeff VanderMeer I see that John Klima is competing in the Pepsi ‘Good Idea’ competition with his “Other Worlds” project, an SF magazine showcasing underrepresented cultures.

Right now, his idea ranks 234, and only the top ten get funding. So spread the word and vote!

Optimism in literature around the World and SF in Particular, part 6: Israel

After a hiatus that was longer than planned, here’s the sixth installment of this series:

Optimism in Israeli SF

By Lavie Tidhar

Israeli science fiction, such as it is, is founded on the most optimistic of novels — Theodore Herzl’s Altneuland, published in 1902. Altneuland (Old-New Land: full text of the English translation here), is a utopian vision of a Jewish state in Palestine, then a part of the Ottoman Empire. Herzl was the founder and leader of Zionism, the movement seeking to establish a national home for the Jews. It is interesting to note that many alternatives to Palestine were suggested at one point or another (including land in Syria, Egypt, South America, the United States and British West Africa), with Herzl negotiating opposite the British government and the Ottoman Empire, but without results.

Israeli science fiction, such as it is, is founded on the most optimistic of novels — Theodore Herzl’s Altneuland, published in 1902. Altneuland (Old-New Land: full text of the English translation here), is a utopian vision of a Jewish state in Palestine, then a part of the Ottoman Empire. Herzl was the founder and leader of Zionism, the movement seeking to establish a national home for the Jews. It is interesting to note that many alternatives to Palestine were suggested at one point or another (including land in Syria, Egypt, South America, the United States and British West Africa), with Herzl negotiating opposite the British government and the Ottoman Empire, but without results.

Altneuland was Herzl’s futurist manifesto, a utopian novel following two protagonists, a Jewish intellectual and a Russian aristocrat, as they visit Palestine first in 1898, when it is a desolate place, and then twenty years later, when they discover a Jewish utopia had emerged during their absence. In the typical fashion of utopian novels, they then go on a guided tour of this new society.

As a novel, perhaps, Altneuland lacks literary merit. As a vision of a then non-existent future, and as a rallying cry for the establishment of a Jewish state, it has been remarkably influential, though Herzl’s vision of a peaceful Palestine did not come about…

In the novel, the port city of Haifa is the main urban centre, electricity powers homes, trains run throughout the country, and European cultural institutes — an opera house, theatres, etc. — are commonplace. The inhabitants speak German rather than Hebrew or Yiddish. And a Third Temple has been built in Jerusalem…

Incidentally, the Hebrew translation of the book, as Tel Aviv, would lend its name to a newly-established suburb of Jaffa, later to become Israel’s main city: Tel Aviv.

Incidentally, the Hebrew translation of the book, as Tel Aviv, would lend its name to a newly-established suburb of Jaffa, later to become Israel’s main city: Tel Aviv.

Herzl’s novel is itself pre-dated by an earlier utopia, and the first in Hebrew —

Elhanan Levinsky’s mostly forgotten A Journey to Israel in the Year 2040, published in Poland in 1892. Again, there are electric lights, bustling ports — and airships!

The establishment of a Jewish state in what was by then British Mandate Palestine (The British won it from the Ottomans in First World War) did not go quite as planned. Conflict with both the British, and the Arab population of Palestine, proved costly and increasingly bitter, and the eventual foundation of the State of Israel was done only after the first of many subsequent wars. And over all fell the shadow of the war in Europe and the Holocaust, forever imprinting itself into the collective Israeli psyche.

Which meant optimism in fiction, despite its hopeful beginnings, might have been in short supply.

Israeli literature has always been more concerned with the here-and-now than with the — increasingly uncertain — future. Such stories fitting into a science fiction and fantasy mould were published almost exclusively as children’s books. Perhaps the most notable of these were the three books written by Eli Sagi: The Adventures of Captain Yuno, published between 1963 and 1964. The books follow the adventures of two children, Yuno and Vena, as they stowaway on an Earth spaceship and then become involved in a series of adventures throughout the solar system, in which each planet is populated by different alien races. Earth itself is a sort of utopia, run by the United Nations — and Earth’s space programme is headed by none other than one Professor Asimov… With wonderful illustrations by the master of the Israeli children book, M. Aryeh, the books are nevertheless almost unknown today, and the nearly 50-year old copies fetch high sums — if one can find them at all. Sagi, incidentally, went on to become a successful playwright and, in the 1980s, was the creator of The Big Restaurant, a Hebrew-Arabic sitcom set in a restaurant in Jerusalem which was successful, it was said, across the whole of the Middle East.

The Adventures of Captain Yuno, alas, did not extend beyond the first three books – a fourth book was listed but never published. It is itself pre-dated by The Mystery of the Flying Saucer, by Menahem Talmi, published in 1955, in which a boy from Tel Aviv goes on a journey to Mars and other planets, and experiences the utopian societies of the aliens.

The Adventures of Captain Yuno, alas, did not extend beyond the first three books – a fourth book was listed but never published. It is itself pre-dated by The Mystery of the Flying Saucer, by Menahem Talmi, published in 1955, in which a boy from Tel Aviv goes on a journey to Mars and other planets, and experiences the utopian societies of the aliens.

Science fiction only really became widespread in the 1970s — the Hebrew term for SF had to be negotiated first, the earlier “Mada Dimyoni”, or imaginary science, leading at last to “Mada Bidyoni”, or fictional science — and the most important event in this nascent field was the establishment, in 1978, of the first genuine Israeli SF magazine, Fantasia 2000. It was an act of pure, unadulterated optimism, by four young students who, later, would admit that had they known what they were doing they would never have done it in the first place. Nevertheless, the magazine not only came into being but continued for an unparalleled 44 issues over 6 years, translating many of the classic American stories of the genre (but also the occasional French and Russian) and offering the first ever stage for Israeli writers themselves. Though some — many — of the Hebrew stories published in the magazine were not of a very high calibre, some still delight – particularly Mordechai Sason’s “The Beggar and the Tin Man”, about a future Israel in which robots beg on the street and are pursued by the malevolent bank, who wants to destroy them — but in which the Israeli public takes up their cause instead, with both hilarious and thought-provoking results. Another writer making his debut in the pages of Fantasia 2000, Amir Gutfreund, would later become the author of the critically and commercially successful Shoa Shelanu (Our Holocaust) and other novels, and win the prestigious Sapir Prize in 2003.

The 1980s saw the demise of Fantasia 2000 and a long period of drought in Israeli SF that would be, ten years later, spectacularly revived. Of the handful of science fiction books published in the 1980s, however, special mention should be made of another utopia, and perhaps one of the most interesting — and certainly controversial — of Israeli SF novels. Luna: The Genetic Paradise was published in 1985, written by geneticist Ram Mo’av as he was dying of a terminal illness. This extraordinary novel tells the story of a dying scientist who is given the ability to view the future via a device called the Camera — specifically, the future of a utopian settlement on the moon, in which principles of eugenics determine immigration, births and much more. The novel is at the same time a searing indictment of Israeli society — at one point depicting Israeli-born children, or sabras, tormenting the nameless narrator (a Holocaust survivor), in which they are compared to the Nazis — and the story of a multicultural, utopian society on the moon based, as mentioned, on the somewhat dubious arguments of eugenics. While not necessarily a good novel — like Altneuland before it — it is a fascinating novel, though once again its influence may be negligible: as with the previous books mentioned, it is very hard today to locate a copy.

The 1980s saw the demise of Fantasia 2000 and a long period of drought in Israeli SF that would be, ten years later, spectacularly revived. Of the handful of science fiction books published in the 1980s, however, special mention should be made of another utopia, and perhaps one of the most interesting — and certainly controversial — of Israeli SF novels. Luna: The Genetic Paradise was published in 1985, written by geneticist Ram Mo’av as he was dying of a terminal illness. This extraordinary novel tells the story of a dying scientist who is given the ability to view the future via a device called the Camera — specifically, the future of a utopian settlement on the moon, in which principles of eugenics determine immigration, births and much more. The novel is at the same time a searing indictment of Israeli society — at one point depicting Israeli-born children, or sabras, tormenting the nameless narrator (a Holocaust survivor), in which they are compared to the Nazis — and the story of a multicultural, utopian society on the moon based, as mentioned, on the somewhat dubious arguments of eugenics. While not necessarily a good novel — like Altneuland before it — it is a fascinating novel, though once again its influence may be negligible: as with the previous books mentioned, it is very hard today to locate a copy.

The 1990s saw the first true flowering of Israeli SF, with the advent of the Internet leading fans and writers to get in touch with each other, and subsequently leading to the formation of an Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy, the establishment of national conventions, and to the rise of a new SF magazine — and the first of its kind to be devoted almost exclusively to original Israeli SF short stories.

Chalomot Be’aspamia (the expression can be loosely translated as “pipe dreams” or “daydreams”) was began as a fan initiative but was taken over by Ron Yaniv as publisher, leading to the first magazine since Fantasia 2000 to be distributed in Israeli bookshops. It was edited by Israeli writer and translator Vered Tochterman from issue 1 to 16 (plus a special themed issue, the first original shared-world anthology to be published in Israel), and by Nir Yaniv from 17 to the current issue 20. Another optimistic gesture, the magazine published a wide range of stories and writers but is currently on hiatus, with its future uncertain — though at least one more issue, number 21, is projected to appear. It is interesting to note, incidentally, that the magazine came a full circle recently by publishing, in its issue 19, a story by an older Amir Gutfreund — the only writer thus to be published in both Fantasia 2000 and Chalomot Be’aspamia.

Bur what does the future hold for Israeli SF? While it is unreasonable to assume speculative fiction will ever have a large number of writers in Israel, the future does look hopeful. A new generation of writers is experimenting with short stories and publishing new novels, some with more impact then others. There are now conventions, web sites, forums, even writing workshops devoted to genre fiction. The future, as it is wont to do, remains to be seen.

Bur what does the future hold for Israeli SF? While it is unreasonable to assume speculative fiction will ever have a large number of writers in Israel, the future does look hopeful. A new generation of writers is experimenting with short stories and publishing new novels, some with more impact then others. There are now conventions, web sites, forums, even writing workshops devoted to genre fiction. The future, as it is wont to do, remains to be seen.

Lavie Tidhar is the author of linked-story collection HebrewPunk (2007), novellas Cloud Permutations (2009), An Occupation of Angels (2010), and Gorel & The Pot-Bellied God (2010) and, with Nir Yaniv, of The Tel Aviv Dossier (2009). He also edited the anthology The Apex Book of World SF (2009). He’s lived on three continents and one island-nation, and currently lives in Israel. His first novel, The Bookman, is published by HarperCollins’ new Angry Robot imprint, and will be followed by two more.

Lavie Tidhar is the author of linked-story collection HebrewPunk (2007), novellas Cloud Permutations (2009), An Occupation of Angels (2010), and Gorel & The Pot-Bellied God (2010) and, with Nir Yaniv, of The Tel Aviv Dossier (2009). He also edited the anthology The Apex Book of World SF (2009). He’s lived on three continents and one island-nation, and currently lives in Israel. His first novel, The Bookman, is published by HarperCollins’ new Angry Robot imprint, and will be followed by two more.

Tentative Steps Forward: West Africa, North Australia, San Francisco, Brazil, the World

Sometimes I can’t help but wonder why—in the SF blogosphere —a post about whether SF should or should not die effortlessly draws more eyeballs than near-future SF stories that demonstrate its relevance. Partly, I suspect, because stories do not contain links to other articles. Still, it’s a bit of a shame that articles with a negative undertone get more attention than stories with a positive message. Or maybe I’m just comparing apples to pears.

Therefore an article about positive developments in the world (I’ve already posted plenty of those). Here’s one development that particularly caught my attention, because it is a solution that addresses several problems at the same time:

→In West Africa, native fruits have a big future:

(from New Scientist, November 7, 2009. Yes, it’s six weeks old, and I’m catching up on my NS reading. But this is an item that will remain relevant for—at least—several decades, showing that near-future, optimistic SF does not need to have a one or two-year expiration date.)

For those not subscribing to New Scientist, the article is online.

To quote:

“Domesticating wild fruit like bush mango has changed our lives.”

“It is a peasant revolution taking place in the fields of Africa’s smallholders.”

In short, African farming smallholders are switching to local wild fruits, making both more food and more money, and creating more biodiversity and environmental sustainability in the process.

The advantages combine to make a sum larger than the separate parts:

- fruit trees exist in a large variety (over 300 different ones in Cameroon alone);

- fruit trees are much better resistant against droughts than mass crops like cassava, maize and wheat;

- in the domestication programme, local knowledge and science—after some initial mistrust, which was overcome by the good results—are combined;

- all low-tech, no fancy equipment needed;

- fruit trees generate income year-round (not just three months like, for example, cacao);

- they thrive in a diversity situation (many different tree crops on one land), creating a habitat for wildlife and environmental sustainability;

- people not only get better food, but with the extra income they buy school fees for their children, decent healthcare, and improved housing;

Let’s call it ‘win/win squared’!

Obviously, there is still a very long way to go, and there will be large obstacles to overcome—especially worries about a level playing field against big agriculture: check out some of the comments in the comment section—but this is nevertheless a tentative step forward, not only in Africa, but it’s happening in North Australia, as well (see also some of the comments in the comment section of the article).

A similar interesting development is the rise of urban beekeeping as honeybee numbers have been falling to catastrophic levels, with the counter-intuitive result that people in cities are helping to keep honeybees alive, both genetically and increasingly in larger numbers. Many thanks to Cameo Wood—who runs Her Majesty’s Secret Beekeeper in the Mission District—for informing me about this when she showed Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman and me around in San Francisco, courtesy of Borderlands Books.

These are just two examples of how important changes can arise from small origins, and not necessarily need to come from big technological shifts.

These are just two examples of how important changes can arise from small origins, and not necessarily need to come from big technological shifts.

By way of contrast, two examples of implementing change directly on the larger scale (keeping in mind that the previous examples are already adding up in sheer numbers):

- Growing biofuel without razing the rainforest (also via New Scientist): an interview with plant scientist Marcus Buckeridge;

- The 2009 Human Development Report: common migration misconceptions are challenged (“Migration can be a force for good, contributing significantly to human development,” says United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Administrator Helen Clark.)

To restate (as I’ve done over and over on this site): good things and optimistic developments are happening on this planet: they’re just underreported, underrated and—I suspect—underestimated. Let’s keep looking forward, and work on a better future.

Should SF Die?

(Cross-posted to my personal blog and the DayBreak Magazine site for those who prefer a more Spartan layout.)

There’s been a lot of musing about the fate of science fiction, lately. To be clear, I’ll be discussing *written SF* here (predominantly), not SF in movies, comics, video games or other media. To summarise (and this is far from complete, but I hope it touches upon the main points):

- According to Ashok Banker, SF is morally and ethically bankrupt (to put it mildly: his interview at the World SF News Blog has been deleted on his request, because some idiot stalker is now threatening not only him, but his family and friends, as well);

- According to Lavie Tidhar, SF — and fantasy, as well — is suffering from monolithic anglophone syndrome;

- According to Mark Newton, SF is commercially dead, and fantasy is the (bestselling) future;

- According to Athena Andreadis on the Huffington Post, SF has ditched science and has become, in effect, fantasy. Geoff Ryman (who recently edited When It Changed) and Ken MacLeod (who is involved with The Human Genre Project) seem to agree;

My viewpoint is that SF is becoming increasingly irrelevant, and that lack of relevance can be attributed to developments and trends already mentioned in the points above, and SF’s unwillingness to really engage with the here-and-now. That doesn’t mean that SF needs to die (actually, a slow marginalisation into an increasingly neglected and despised niche-cum-ghetto is probably a fate worse than death), but it does mean that SF needs to change, and that it needs to become much more inclusive of the alien (and I mean alien in ‘humans-can-be-aliens-to-each-other’ sense) and proactive, meaning it should not just shout ‘FIRE! FIRE!’ (and do almost nothing but), but both man the fire trucks *and* think of ways to prevent more fires.

That’s the short version: allow me to expand on it below the cut. Read the rest of this entry »

That’s the short version: allow me to expand on it below the cut. Read the rest of this entry »

Kindred Spirits, part 9

In all the kerfuffle I haven’t failed to notice Terry Bison’s interview with Kim Stanley Robinson (regular visitors know I’ve quoted the man several times on this site already). Io9 summarised it as “Dystopian Fiction Is For Slackers“, and while I mostly agree — while acknowledging that there are great dystopias, I think the form itself has become too much of an easy writing mode and a cliché — I think it oversimplifies matters.

As Kim Stanley Robinson said on the New Scientist website earlier this year, science fiction tends to see the pessimism/optimism duality too much as an either/or phenomenon, while in real life things are much more complex: they’re a mix of upbeat and downbeat, with indifference, incomprehensibility and interconnectedness thrown in for good measure, and also strongly subjective; that is dependent on and coloured by one’s personal experience, mindset and perspective.

And indeed, while he calls it ‘utopia’, what he means is not a full-on, happy clappy Pollyanna:

So, the writing of utopia comes down to figuring out ways of talking about just these issues in an interesting way; how tenuous it would be, how fragile, how much a tightrope walk and a work in progress.

This, BTW, describes the majority of the stories in both the Shine anthology and DayBreak Magazine. One clear example that you can already read is David D. Levine’s “horrorhouse“, that perfectly demonstrates ‘how tenuous, fragile’ such a ‘utopia’ (I prefer to call it a ‘better future’, meaning there’s always room for improvement, with ‘utopia’ as the ideal that can never quite be reached) is: both a ‘tightrope walk’ and always a ‘work in progress’.

Finally, I take note that if people thought that I overstated my case with the “Why I Can’t Write a Near-Future, Optimistic SF Story: the Excuses” piece (which keeps consistently getting several dozens of hits each day), well, Kim Stanley Robinson doesn’t exactly pull his punches, either:

The political attacks are interesting to parse. “Utopia would be boring because there would be no conflicts, history would stop, there would be no great art, no drama, no magnificence.” This is always said by white people with a full belly. My feeling is that if they were hungry and sick and living in a cardboard shack they would be more willing to give utopia a try.

Amen to that.

(Or, as I said: “And indeed, that’s what most dystopias are: a comfort zone for unambitious writers”.)

While some do see the opportunities in utopias (and watch this space come March 19, 2010), others immediately feel the need to defend dystopias. As if these, like climate change, need defending.

Anyway, one small blessing has already occurred: new e-zine Bull Spec — whose first short is by Terry Bisson, indeed who did the ‘utopia’ interview: coincidence? — already changed their guidelines to include utopias on the theme:

“utopias are hard, and important, because we need to imagine what it might be like if we did things well enough to say to our kids, we did our best, this is about as good as it was when it was handed to us, take care of it and do better. Some kind of narrative vision of what we’re trying for as a civilization.”

(Which is a straight quote from the Galileo Dreams interview.) So one more market — keep track: such markets are thin on the ground — where to send an optimistic story (when they re-open on February 1 next year).

Apropos David D. Levine’s “horrorhouse“, another interesting ‘coincidence’: a few days ago New Scientist put an article called “How reputation could save the Earth“, where the influence of maintaining a good reputation is wielded to extract good (eco-friendly) behaviour:

If information about each of our environmental footprints was made public, concern for maintaining a good reputation could impact behaviour. Would you want your neighbours, friends, or colleagues to think of you as a free rider, harming the environment while benefiting from the restraint of others?

Compare this to the EcoBadge in David’s story, which was published 17 days before the New Scientist article, demonstrating that near-future SF can both be trend-setting and not age immediately.

Blueprint for a Better World

Which is literally what New Scientist is saying in their weekly newletter to me (and I’m a longtime subscriber), here.

I know I’ve said this before (a lot of times, maybe to the point of ad nauseam), but I’m afraid it needs to be repeated, especially for a lot of thick-headed people in SF: people around the world want more than just the next doomsday scenario telling them what happens of we carry on doing the *stupid* things: what they really want (and need) is a pointer to solutions.

I know I’ve said this before (a lot of times, maybe to the point of ad nauseam), but I’m afraid it needs to be repeated, especially for a lot of thick-headed people in SF: people around the world want more than just the next doomsday scenario telling them what happens of we carry on doing the *stupid* things: what they really want (and need) is a pointer to solutions.

I really need to refrain from quoting the whole piece (“Blueprint for a Better World“) verbatim. But it’s what I’ve been saying on this very blog from the get-go. Like:

We live in an imperfect world. Poverty, disease, lack of education, environmental destruction – the problems are all too obvious. Many people don’t have clean water, let alone enough food, and the unsustainable lifestyle of the wealthy few is storing up catastrophic climate change.

Can we do anything about it? You bet we can. Technology is a double-edged sword, but science and reason have made our lives immeasurably better overall – and only through science and reason can we hope to make a real difference in the future. So here and over the next three weeks, New Scientist will explore diverse ideas for making the world a better place, and the evidence backing them.

Almost exactly as in some stories in Shine, [in part 1 this week] “we look at some radical ideas for transforming society and changing the way countries are run”.

[Next week in part 2] “We’ll report on what you as an individual can do to make a difference.” I can point to a few other stories in Shine.

[In part 3] “We’ll explore what many see as the fundamental problem: overpopulation.” Kill me, shoot me and throw me to the wolves, but please check out The Elephant in the Room: a Foreshadowing (from December 1, last year) first.

[In part 4] “We’ll ponder the profound and long-lasting changes we are making to our home planet.” Again, I can point to several Shine stories.

Yes, I’ve delivered the final MS (manuscript) to Solaris Books. The people at Solaris are now very busy with the owner transition I mentioned in the previous post. So while I’m awaiting more info from them (release date, for one), I am confident that they will publish Shine (as per contract, and—more importantly—per intent). Apologies for the lack of replies in the past week, as I am working on several other things, which will become clear as they happen.

And no apologies as I need to ram home the really important thing: the majority of SF, and the majority of written SF in particular, sees no need in portraying a future ‘where people might actually like to live in’ (as Gardner Dozois has it in the July 2009 Locus). On the other hand, the most popular weekly scientific journal in the world DEDICATES FOUR ISSUES TO DEPICT “A BLUEPRINT FOR A BETTER WORLD”.

Now who is out of touch here?

Now who is out of touch here?

I’m very, very happy with what New Scientist is doing right now. I would be completely ecstatic if Shine would appear right after that, but it seems it’ll be early 2010. Compared by how fast written SF moves, though, it’ll still be bleeding edge.

Crazy Story Ideas, part 4A: Ageing in the EU

I mentioned that overpopulation is the elephant in the room. I mentioned I would be getting back to this point.

So here’s the comeback, initiated both by an article in a recent New Scientist issue where Sir David Attenborough spells it out, and last week’s “Planetary Boundaries and the New Generation Gap” article on Worldchanging.

Attenborough summarises the biggest problem (and why he’s a patron of the Optimum Population Trust):

There are nearly three times as many people on the planet as when Attenborough started making television programmes in the 1950s – a fact that has convinced him that if we don’t find a solution to our population problems, nature will. “Other horrible factors will come along and fix it, like mass starvation.”

World Changing talks about the huge complexity of the intertwined problems, at length, as well. However, they think we can solve our main problems:

There are plenty of reasons for despair and cynicism these days. But it’s really important not to underestimate the power of the politics of optimism, the power of actually having better ideas and answers. They are especially powerful when the people opposing us have nothing whatever to offer besides a white-knuckled grasp on a broken status quo. Their only weapons are fear, uncertainty and doubt. It’s time we counter with optimism, vision and examples. We need to counter with a future that works.

(Emphasis mine.)

We need to deal with overpopulation, and we need to deal with it in a humane way. So I am not going to accept stories where most of the world’s people are killed off in order to save the rest, or save the planet (even if we published a story like that in Interzone, “Blue Glass Pebbles” back in #205 of August 2006).

No easy way out (in a storytelling sense): thus no fabricated virusses decomating humanity, no pandemics reducing the population. Population growth needs to be curbed.

If current trends continue, we will reach a peak population of about 9 billion people in 2050, before the population will finally start to shrink. As World Changing already mentioned: “one of our biggest goals ought to be seeing to it by every ethical means possible that the wave of population growth crests sooner rather than later.”

One important way of doing that is by empowering women. Another way of curbing population growth is by increasing wealth worldwide. Because there are already countries where the population is shrinking, right here on the continent where I live: Italy, Germany, Spain, The Netherlands and even the UK. Admittedly the population of these countries is still increasing, but this is through immigration. But reproduction rates in these countries have fallen below the ‘replacement rate’, that is, more people die – one hopes from ‘natural’ causes – than are born (or sub-replacement fertility levels).

This has the following effects:

- the median age of the population will rise (not only because of a decreased birth rate, but also because of increased longevity);

- the age distribution of the population will change drastically;

- hence, the old economic model of continuous growth will need to change to a ‘zero growth’ model;

- Also, a change – hopefully gradual – from a society that mines limited resources to a society that works at a (close to) 100% recycling rate;

Politically conservative forces (who, if they were really about conservation, should be championing green policies like mad) will baulk at the prospect of a shrinking population, mired as they are in the old ways of thinking: the economy should *always* grow, the young should take care of the old, so we need more young people than old ones. Now this is where SF – supposedly the literature of change – comes in: we need to imagine a society with a shrinking population that works. And the place that is at the forefront of that particular dynamic is the European Union.

So why not imagine a story about ageing in the EU.

(Actually, people outside SF are already thinking in that direction. I particulary remember a special ‘future’ issue of Dutch magazine Intermediair – which is basically a carreer-oriented magazine for the well-educated – of about a year ago that predominantly dealt with the effects of an ageing population. It’s not online, AFAIK.)

For one, showing that an ageing society with a sub-replacement fertility rate works sets a good example to the developing world. Quite simply because it would be extremely hypocritical of the West to ask of the developing world to reduce their fertility levels if we weren’t doing it ourselves, and it would hugely help this all-important cause if we can show them that such a society is a happy one.

Thus, the EU not only needs to deal with an ageing population and its subsequent demographics, but make it a shining example, as well.

First thing is to ditch with the contemporary cultural notion that young = cool and old = uncool. It’s bullshit: young and old are just different stages in a human life. Both have their pros and cons, and while the pros of youth have been widely overexposed, it’s time to set the spotlight on the pros of maturity.

For one, as Bruce Sterling chimes in at Beyond the Beyond: an ageing population isn’t apt to support extremist movements. He surmises it’s “Not because we’re any smarter, but because we lack the brio”. Hm: I greatly disagree. My mother, now 72, is still very active and helps out handicapped people on a Red Cross boat. What I suspect is that this older demographic might indeed be a bit wiser – on average – and just won’t put up with it.

Also, as longevity increases I see a lot of active retirees in my direct environment. Like my mother, they do huge amounts of volunteer work. Actually, women – on average – live longer than men, so we’ll be seeing an increased amount of active, experienced and – dare I say – wiser women. Which is, I think, certainly not a bad thing: rather the contrary.

For another, what happened to the way of thinking that tried to turn a liability into an assett? For example, we need to do away with the ingrained notion that a healthy economy must grow, grow, grow forever. It should be abundantly clear by now that we live on a planet with limited resources, so the most logical answer to deal with those resources is a ‘zero-growth’ or ‘steady-state’ (the latter is from the early 70s: so it’s not a new idea) economy.

Thus, the EU with its ageing population needs to change over to a zero growth model anyway (and its economic growth was already relatively low, which did not hamper the quality of living in Europe: rather the contrary).

Also, while we’re at it, it’s also in the EU’s (and the world’s) best interest to, indeed, develop the developing countries. So the EU should take down its tariff walls first and foremost. Yes, this will adversely affect several EU industries and the agricultural sector. But both need to adapt to the new circumstances, and it better to do this sooner rather than later (as is demonstrated by the three big car industries in the US).

Also, the EU should invest heavily in placing huge solar cell plants (like those already made in Germany and Spain) in the Sahara: this benefits both Africa and Europe. It will help develop Africa, bringing wealth to it, and remember that wealthy societies tend towards sub-replacement fertility rates and that population growth is highest in Africa. It will increase green energy production (and oil independency) on both continents, and generate labour and economic activities as those plants are being built, and huge power cables are laid across the Meditarranean.

I can see a forerunner role for Spain and Morocco in this: for one, Spain already knows how to make huge solar collectors; for another the distance between spain and Morrocco is the smallest (the Strait of Gibraltar is about 20 kilometres wide), and finally they can do a political/economical tit-for-tat: Spain releases its claim on the Western Sahara in exchange for a hundred year warranty of energy delivered at a premium price.

Then Italy and Greece can make similar energy connections to Libia and Egypt, France can use its old ties with Algeria for a similar energy synergetic connection.

In short: yes, there will be a peak population. This is the bottleneck the world needs to pass through. However, we can try to minimalise the effects of that bottleneck twofold:

- Work on making that population peak lower than 9 billion;

- Work on making that population peak happen sooner than 2050;

And at the same time accelerate the change-over to a sustainable, green economy which will not only help us pass through that bottleneck with minimal damage, but also pave the way for the new society behind it.

This is getting a bit long, so I’ll be doing the actual *story* idea in part 4B, which I hope to post before, or over the weekend.

UPDATE: (OK: part 2 is delayed. I’m busy.) Just in today via De Volkskrant: “Agreement about Solar Power from the Sahara“. Article in Dutch, but links to the Desert Industrial Initiative, and I see that ABB is involved, as well. Together with Siemens (mentioned in the paragraph below), these are two of the absolute top technological companies in the world (yes: I know this from direct experience in the day job). So this is *very* serious business, indeed!

But the gist of it: a consortium of mainly German companies — Siemens, RWE, Eon, Deutsche Bank, Münchener Rück (a re-insurance company) and Cevital (an Algerian food company), amongst others — want to supply 15% of Europe’s energy from solar power in the Sahara by 2050. Check out the awesome concept on this PDF file.

OK: so I predicted it would be Spanish, Italian, Greek or even French companies, but was wrong: it’s the Germans who want to go there first. Nevertheless, the idea is sound, and yet hardly anybody (to the best of my knowledge: do absolutely feel free to correct me) dares to use this — sorry to say — fairly straightforward prediction in their science fiction.

OK: so I predicted it would be Spanish, Italian, Greek or even French companies, but was wrong: it’s the Germans who want to go there first. Nevertheless, the idea is sound, and yet hardly anybody (to the best of my knowledge: do absolutely feel free to correct me) dares to use this — sorry to say — fairly straightforward prediction in their science fiction.

It’s not *that* hard, right? And in my very outspoken opinion most readers will *remember* a story for making a correct prediction about the principle (Europe receiving huge amounts of solar power from the Sahara, benefitting both Africa and Europe), and *forgive* the very same story for getting the details wrong (it’ll be German/Algerian companies instead of Spanish/Moroccon ones).

So, you SF writers out there: do you still dare?

Optimism in Literature around the World and SF in Particular, part 5: Brazil, “the Country that Could Have Been and Maybe Will”.

In this ongoing series Jacques Barcia portrays his home country Brazil:

The country that could have been but maybe will.

By Jacques Barcia

Author Ian McDonald, when talking about his latest novel Brasyl, said the South American giant has always been the country of the future. That’s an epithet that every Brazilian knows by heart for it goes back to the post-war days and through the age of mass industrialization in the 1960s. An idea that became part of our national identity. The idea of being almost there, almost reaching the echelons of economic superpower, being just a few steps away from the First World. And getting closer. Forever getting closer. From the 60s to the 70s, then 80s, 90s and crossing to the 21st century, Brazil has been forever getting closer. But maybe now, Brazil’s fulfilling that prophecy. Or getting closer than ever.

Not surprisingly, this cultural aspect has everything to do with the way science fiction has presented itself in the country for the last 40 years and how, today, it may change.

Brazilian SF has always been pessimistic. Worse yet, in many occasions it has been ironical to the very idea of future. The 70s and early 80s, the “age of lead”, as we call it, because of the military dictatorship on course, were marked by the publication of some classic dystopian novels, like “And Still the Earth” (originally Não Verás País Nenhum, or You`ll See no Country) by Ignacio de Loyola Brandão. A decade later, when cyberpunk finally arrived in Brazilian bookstores, it quickly grabbed readers and writers alike because, well, Brazil IS a cyberpunk country. And as the original punks would say, there’s no future.

Brazilian SF has always been pessimistic. Worse yet, in many occasions it has been ironical to the very idea of future. The 70s and early 80s, the “age of lead”, as we call it, because of the military dictatorship on course, were marked by the publication of some classic dystopian novels, like “And Still the Earth” (originally Não Verás País Nenhum, or You`ll See no Country) by Ignacio de Loyola Brandão. A decade later, when cyberpunk finally arrived in Brazilian bookstores, it quickly grabbed readers and writers alike because, well, Brazil IS a cyberpunk country. And as the original punks would say, there’s no future.

Crime rates are really high. Last year in my home city, a 3 million people metropolis, there were about 4,000 homicides. Literacy rates are very low and many live in extreme poverty. That lack of perspective, high crime rates, political corruption and years upon years of repression from the military dictatorship made Brazilian people (and Brazilian SF writers) believe that the country of the future would be even darker than it already was. Or that future was a very bad joke.

But this same country of extreme conditions is hopefully getting better. There’s less extreme poverty, there’s more education, and general conditions are way better than ten years ago. And even though there are still extreme problems to be faced, there’s an interesting thing going on. Brazilians, especially the poorest, are in love with technology. By the numbers, there are more active cell phone lines than living Brazilians. Everybody has a cell phone. Everybody is on Orkut (you know, that social network from Google). Everyone has a flog, uploads videos to Youtube, shares MP3s, even the illiterate. And though the vast majority of people can’t afford a PC, Brazilians hold the world record for hours spent online per month per capita (24h07 in average).

But this same country of extreme conditions is hopefully getting better. There’s less extreme poverty, there’s more education, and general conditions are way better than ten years ago. And even though there are still extreme problems to be faced, there’s an interesting thing going on. Brazilians, especially the poorest, are in love with technology. By the numbers, there are more active cell phone lines than living Brazilians. Everybody has a cell phone. Everybody is on Orkut (you know, that social network from Google). Everyone has a flog, uploads videos to Youtube, shares MP3s, even the illiterate. And though the vast majority of people can’t afford a PC, Brazilians hold the world record for hours spent online per month per capita (24h07 in average).

Again, that has everything to do with SF literature. Brazil was cyberpunk and it’s becoming post-cyberpunk. If Brazil used to have marginal tech with a dirty, gritty and violent setting, now the country is techy, edgy, and hopeful. There are tons of examples of how things could get better with technology and how literature could represent those facts and hopes in fiction.

For example, 3G networks are used in public web-based long-distance education programs. Computer games (like Civilization) are used in many schools to teach history, political science, administration, etc. Indigenous tribes use the web to preserve their cultural heritage. Almost-forgotten languages are available online, as well as ritual dances.

For example, 3G networks are used in public web-based long-distance education programs. Computer games (like Civilization) are used in many schools to teach history, political science, administration, etc. Indigenous tribes use the web to preserve their cultural heritage. Almost-forgotten languages are available online, as well as ritual dances.

Another example: Brazil has cars running 100% on alcohol since 1979. Total-flex cars are sold since 2003, a technology developed by Brazilian engineers. Brazilian alcohol comes from sugarcane which has lower impact than corn alcohol. The blend commonly called E25 (that is, 25% of alcohol and 75% gasoline) is the standard of Brazilian gasoline. Brazilian energy comes mostly from hydroelectric power plants and there are projects to build fields of wind turbines in the country’s Northeast.

But unfortunately, Brazilian SF hasn’t realized those facts yet, mostly because established authors are reminiscent of a very depressing age. Maybe the current generation of SF writers, and certainly the next one, will feel more comfortable with imagining a better future. And dreaming with a brighter tomorrow they’ll certainly build a better one too.

But unfortunately, Brazilian SF hasn’t realized those facts yet, mostly because established authors are reminiscent of a very depressing age. Maybe the current generation of SF writers, and certainly the next one, will feel more comfortable with imagining a better future. And dreaming with a brighter tomorrow they’ll certainly build a better one too.

Jacques Barcia is a Brazilian science fiction and fantasy author living in Recife. He has sold microfictions to Outshine and Thaumatrope. He’s currently writing his first novel. He can be reached at jacquesbarcia@gmail.com.